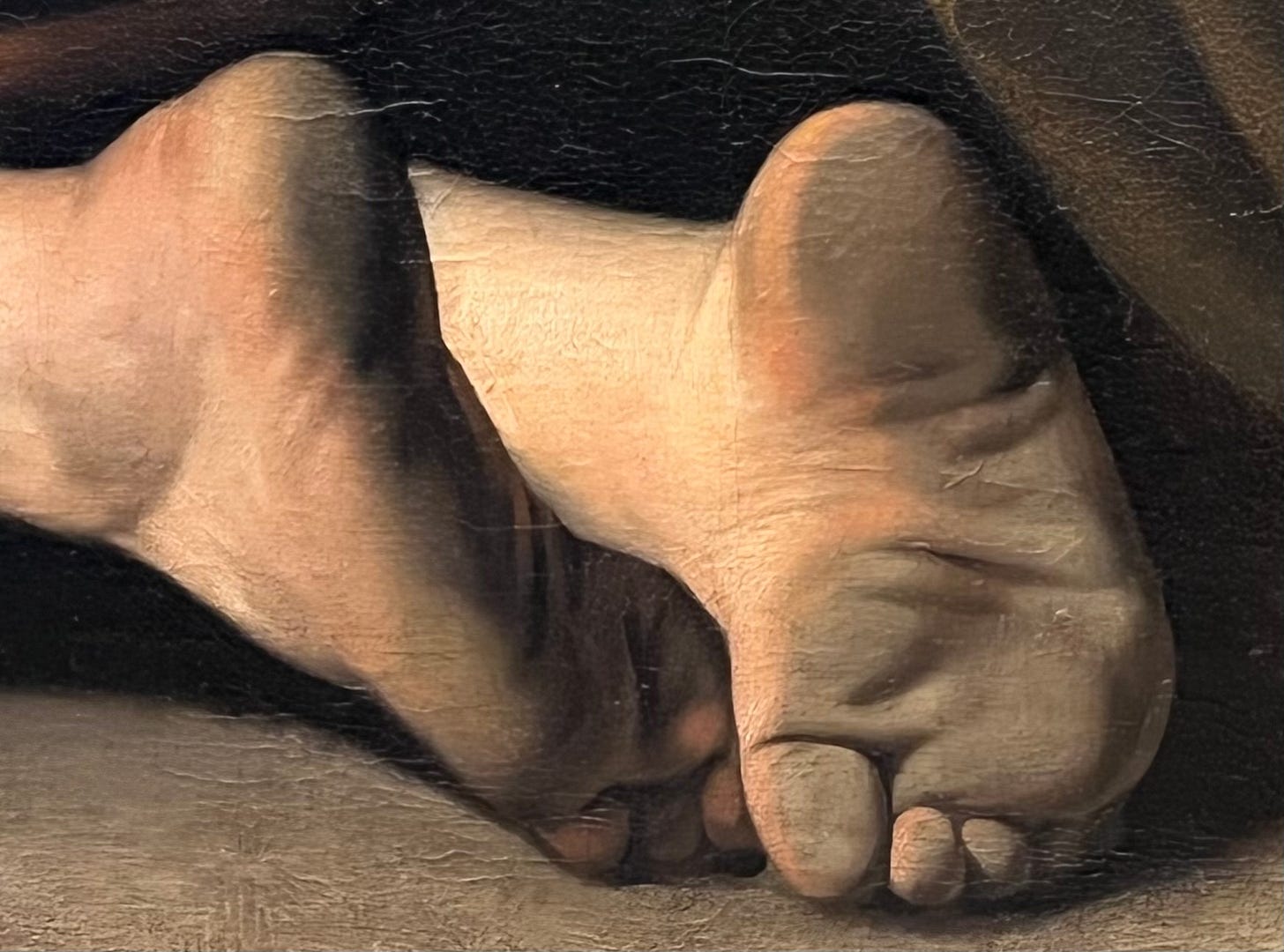

‘After he had finished the central picture of St Matthew and installed it on the altar, the priests took it down, saying that the figure with its legs crossed and its feet rudely exposed to the public had neither the decorum nor the appearance of a saint.’ That was, of course, precisely Caravaggio’s point: Christ and his followers looked a lot more like beggars than cardinals.

~ Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane

Earlier this year, I asked a myeloma expert for an opinion about a question that has nagged me to no end for years: Should the fact that a celebrity has myeloma, or any cancer, disease, or disability, matter when it comes to how it is perceived by the public?

“Yes, it does!”

“No, I didn’t say ‘does it,’ I said ‘should it?’”

“It probably shouldn’t, but it does.”

Why, however, does it when it shouldn’t? I was back to square one with my nagging question.

The first American celebrity with myeloma I could find – my search was by no means scientific or academically rigorous – was Warren William. “Who’s that?” I hear many of you asking. Today he is long forgotten to just about anyone except for TCM junkies like me. (TCM, formerly Turner Classic Movies, is an American cable channel that runs old movies, twenty-four hours a day.)

William was one of the most prolific and recognized leading men in Hollywood spanning the era from pre-code1 Hollywood through the mid-to-late1940s. A trained actor who started out on Broadway, when talkies were beginning to be made, his style and screen presence led to many roles, often playing suave characters, some womanizing, some conniving, some criminal, some witty and charming, sometimes all of them wrapped up together. Combined with his natural, ironic humor, he became a crowd favorite.

On screen, William was the first to portray Perry Mason, a popular criminal defense attorney from Erle Stanley Gardiner novels that became an iconic American television character played by Raymond Burr from the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s. Many movie goers of the time, before the advent of television, attended weekend matinees with playbills of shorts, cartoons, and serials shown before feature films. He was known to many as the star of the Lone Wolf series.

William earned enough to buy a ranch in the San Fernando Valley, then rural, today a bustling urban landscape with few open spaces. During World War II, William, like many actors of the time, was active in USO shows to entertain and boost the morale of soldiers. He was a regular participant in other star-studded events for various causes including for Cedar-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles.

According to his biographer, William’s fortunes changed suddenly by early 1947. “He tired easily, and was having severe bone pain, unable to walk or stand for extended periods. There were bouts of nausea, continuing infections, headaches, and numbness in his limbs.” The combination of not being able to work plus medical costs soon took their toll. He had a few small parts and hoped to work on a new project, but his health continued to decline, baffling his doctors.

Conditions became worse for William later in the year when more than 200,000 in the Los Angeles area came down with what was called Virus X. Although “not fatal, except perhaps to the very young or very old…with his constitution already compromised, Warren’s ability to fight off the disease was problematic.” As his health continued to decline, William was diagnosed with myeloma at Cedars Sinai on December 15, 1947, twelve days after his fifty-third birthday.

His biographer speculated possible exposure to the chemical DDT, which was a commonly used pesticide soon proven to be extremely carcinogenic, may have been to blame. DDT was liberally used on William’s ranch, where he “regularly worked the citrus orchard and walnut groves” in his free time. It was also in the sawdust of his workshop, where he spent hours as a “long-time inventor and tinkerer.”

His tall frame continued to wither, he had to be carried because he couldn’t walk and was soon receiving palliative care. He died on September 24, 1948. There was no treatment at the time, when myeloma was still a mysterious disease, as it would remain for decades to come. His case did nothing to raise awareness or increase research in the disease. When I made Robert Kyle aware of William, he had never heard of him.

In 2015, I corresponded with Pat Killingsworth, a myeloma patient who maintained a website about myeloma until his death on February 11, 2016, about celebrities and obituaries. He believed celebrities diagnosed with myeloma who went public could help raise awareness, bring it to attention to the public and policymakers. Pat told me he had a habit of perusing obituaries to see what cancer people died of and was somewhat upset when they weren’t specific about which type.

A number of celebrities and public figures have been diagnosed with or died from myeloma. But much like Warren William, their memories will fade with time, no matter how important we might think they are. Yet patients – of all cancers and diseases, not just myeloma – experience conflicting emotions when learning of a well-known person’s diagnosis.

First, there’s empathy. No one would wish a disease like cancer on anyone. Then there’s anticipation. Might this raise awareness? Could the details educate others who might have the similar symptoms to seek medical certainty? And then there’s the unspoken hope. Could this help raise more money for research, or prompt policymakers to invest more in it?

I’ve seen this repeat with the diagnoses, just to name a few, of former Secretary of State Colin Powell, Norman Fell (Three’s Company and well-known character actor), Roy Scheider (Jaws), and Peter Boyle (Young Frankenstein and Everybody Loves Raymond, whose widow, Lorraine, is a board member of the International Myeloma Foundation and hosts their annual comedy fundraiser). After former NBC news anchor Tom Brokaw was diagnosed while at a Mayo Clinic board meeting, the network produced many news stories about his diagnosis and treatment progress. And that’s just in the United States.

I addressed this in a letter to The Washington Post, published on March 29, 2024, in response to the public reaction to the cancer diagnoses of King Charles and Princess Catherine in the United Kingdom:

Regarding the March 25 news article “With two senior royals facing cancer, British monarchy must do more with less”:

The announcements by King Charles III and Catherine, Princess of Wales, that they have each been diagnosed with cancer draw attention to two conundrums.

Not revealing their specific diagnoses feeds an obsolete narrative of cancer as a monolithic disease, one universally dreaded, given the perception that patients have only distant hopes of “a” cure. But cancer is a broad term that covers many diseases. Even within subcategories of cancer, patients’ outcomes may vary widely based on genomic characteristics that often require radically differing treatments.

Survival rates for pancreatic and liver cancers, for example, are still dire compared with outcomes associated with early detection and treatment of testicular or skin cancers. In just the past two decades, research on once uniformly deadly cancers such as multiple myeloma and chronic myelogenous leukemia has progressed such that those diseases have become chronic conditions able to be managed for majorities of patients.

On the other hand, there is an almost perverse anticipation among cancer patient interests throughout the world that Charles and Kate will make their specific diagnoses public. Doing so would raise awareness, direct research funds and activity to their cancers, and spur aggressive fundraising efforts for select advocacy organizations.

The ongoing speculation surrounding Charles and Catherine feeds an odd mix of concern, hope, fear and cynicism, underscoring a historical ignorance of how cancer is — or, to be more accurate, cancers are — perceived by the public.

Coincidentally, as I was working on this article, just this past Monday, September 9, news outlets reported that Patty Scialfa, wife of musician Bruce Springsteen, has been treated for myeloma since 2018. Based on my past experience, let me try to peel back the curtain to describe what I believe has been happening during past forty-eight-hours plus – and earlier if some had prior knowledge they have kept confidential.

Patient advocacy organizations are frantically going through their virtual Rolodexes to find anyone who might help make a connection with Scialfa and Springsteen. One may already have the inside track. Logic tells us she’s either being treated at a New York area clinic or one of three major – obvious – cancer centers somewhere in the country. They’ll be checking their contacts with each of them now that the news is public.

The hope will be to get some publicity for their organization – honorees for a gala, stories for websites and annual reports (more about those in a future article), maybe even a Springsteen concert fundraiser – anything to claim credit for a linkage others can’t claim. And monetizing it will be a primary goal.

A major part of this can be attributed to our, and thus, the media’s, obsession with celebrity; of the proverbial style over substance. After all, a public figure is just one person. Why should one person, well-known to some or many, outweigh the experience of large populations?

Take cancer, as a group of diseases, as an example. According to the American Cancer Society’s annual Cancer Facts & Figures 2024, more than 2 million Americans will have been diagnosed with some type of cancer this year alone. That number will go up as the population grows, ages, and lives longer life spans.

By the end of 2022, at least 18 million Americans were living with cancer. And more than 611,000 of them – 1,680 per month – will die from a cancer this year. In myeloma, that translates into more than 35,000 diagnoses, more than 200,000 living with it, and more than 12,500 deaths.

Shouldn’t that be enough to focus our collective attention, create public policies, vigorously fund the sciences, and reign in continued abuses like rampant costs for care and do something substantive about disparities – economic, racial, geographic, or other otherwise? Shouldn’t that be enough to do something about environmental discrimination – knowingly putting peoples’ health at risk to privatize more profit and socialize the costs?

Or providing access to quality care to those in sparsely populated areas? Or about the increased exposure to toxins of farmers, members of the military, first responders, factory workers, or even the people who treat our lawns with chemicals that vastly contribute to the urban runoff that endangers our lakes, streams, coastlines, and aquifers? Or doing something to protect innocent people exposed to seemingly weekly accidents that put them at risk for long-term health consequences?

Sure it comes with a cost. But I already hear the complaints: “Don’t we have already have enough regulations? What about the economy?” Do we ask those questions about military spending, which is at least 37% of global military spending, taking seventy cents out of every dollar of annual federal discretionary spending, leaving just thirty cents per dollar for the entire other federal government?

We should, but we don’t. The possible benefits of the lottery of something happening to a celebrity to focus attention and possible money – other peoples’ money – is much easier and makes better press.

I don’t have all the answers. I’ll try my best to expand on some possible ones in the future.

But for now, we must never stop asking ourselves questions. We may arrive at surprising answers.

Photo: Detail, The Madonna of the Rosary (1607), Caravaggio, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

The Hays Code was inspired by a fear of policymakers that prurience and a disrespect for both the law and law enforcement were being promoted by Hollywood after the introduction of talkies in 1927. As Beverly Gage wrote in G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, “To Hoover’s dismay, the kidnappings and bank robberies of the early 1930s turned out to be ready-made for the film medium, packed with romance, violence, and human drama…some of the earliest talking films lavished their attention and sympathies not on police, but criminals…The film industry had tried to place limits on these pressures by developing a ‘film production code’ under the leadership of former Republican postmaster William Hays, but those rules had proved tricky to enforce…the Motion Pictures Producers suddenly announced…a last-ditch attempt to avoid federal censorship by censoring themselves [in 1934]…Under the codes, pictures that poked fun at authorities or sought to cast aspersions on religion were banned. In their place films would now adhere to a more conservative formula…”