Bookmark This Page!

Remember when the word “myeloma” would have sounded like mysterious jargon? Or when statistics were something only baseball fans and mathematicians cared about? Those were the days.

I’ve met more myeloma patients over the years than I can remember. One thing all have in common is an obsession with statistics and numbers. What are the rates, odds, or percentages of this, that, or the other? I’ve known patients expected to do well only to die within a year. Others who weren’t sure they would be around in the next months are now in their third decade of living with myeloma.

Cancer statistics have a time and place, especially for researchers and physicians. But they don’t have much to say about any individual. I could, for example, flip a coin a thousand times, knowing the result will be close to fifty-fifty. But that experience says absolutely nothing about which side the coin will show after the 1,001stflip. Even the most accurate prediction will be wrong close to fifty percent of the time.

That’s why I always advise patients not to fixate on statistics either as harbingers of doom or reasons for great celebration. They’re just one part of a big, complicated, ever-changing picture, all bundled up in the myeloma of each unique patient.

Like everything in life, there’s an exception to this (my) rule: the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program (NCI SEER) web page. I strongly recommend it be bookmarked by everyone. It provides a concise snapshot of trends and directions. If you know where to look, it tells a rich story of how things were, where things stand, and has hints about the future.

The chart at the top of the page tells the most important story: incidence continues to rise slowly as mortality numbers keep declining. In the dark line at the bottom of the graph, representing annual myeloma deaths since 1992, one can literally see the impact of key therapeutic eras.

A slight rise in deaths in 1993 begins to slowly decline, showing the effects of autologous stem cell transplantation. The descending rate increases slightly after 2000, when thalidomide was followed by Velcade and Revlimid as standard treatments. Another slight flattening of the curve starts descending more noticeably around 2015, when monoclonal antibodies were introduced.

The curve ends at its lowest point in 2022, the most recent year of valid annual statistics. Not yet shown is the impact of newer therapies, including CAR T and bispecific antibodies. Nor the deliberate trend to gradually move them in the direction of frontline treatment, causing many to expect the curve to bend down at an even greater rate in coming years.

Two other numbers add greater significance. The United States’ population in 1992 was 257 million, in 2022, it was 334 million. That means absolute numbers of myeloma deaths went down as the population rose by 77 million people! As the population increases, so will the incidence of myeloma – while, at the same time, the death rate goes down, that seems virtually certain.

Covid added a bit of uncertainty, however. In the top line on the graph, the position of next-to-last square reflects this. Diagnosis rates dramatically decreased just as doctors’ visits did. All diseases, not just myeloma, festered longer in countless under- or undiagnosed cases.

We get a sense of what the cost was by scrolling down to the bottom of the first section, to Prevalence of This Cancer. Slightly less than 180,000 Americans were living a myeloma diagnosis by the end of 2021, about 10,000 more than the year before. Which sounds good until compared with pre-pandemic survival rates. Covid cut the expected number of annual myeloma survivors by about half.

If the post-pandemic trend continues, that would translate into a minimum of 210,000 Americans living with myeloma by the end of this year. Had the pandemic not happened, given the trend at the time, that number would have been expected to be at least 260,000. Three decades earlier, estimated numbers of Americans living with myeloma was about ten percent of those possible extremes in survivorship. Between 21,000 and 26,000.

Far fewer myeloma patients are dying because of Covid-related disease, but it’s likely somewhere in between. Therefore I doubt the lower estimate of 210,000 for 2024 is accurate, but it’s still a good marker. In future years, NCI SEER statistics will provide definitive answers. But looking at the current graph tracking five-year survival rates, the ascent of the curve will likely be steeper than it is now.

Next I would look to the 61.1 % rate of 5-Year Relative Survival based on averages from 2014-2020. In 1995, the rate was 34%, in 1975, it was 26%. As good as the latest NCI-SEER number seems, it is, without question, low. For standard-risk patients treated at university clinics with myeloma specialists, experts regularly predict 90% for ten years, not five.

I would speculate the averages are being brought “down” due in large part to patients who are not treated by or advised by specialists. This is not to denigrate, but to acknowledge the reality that no oncologist can treat all cancer types. Some myeloma specialists treat hundreds of patients a year and consult on countless other cases. A good community oncologist may see one-to-five patients a year; perhaps even over a career.

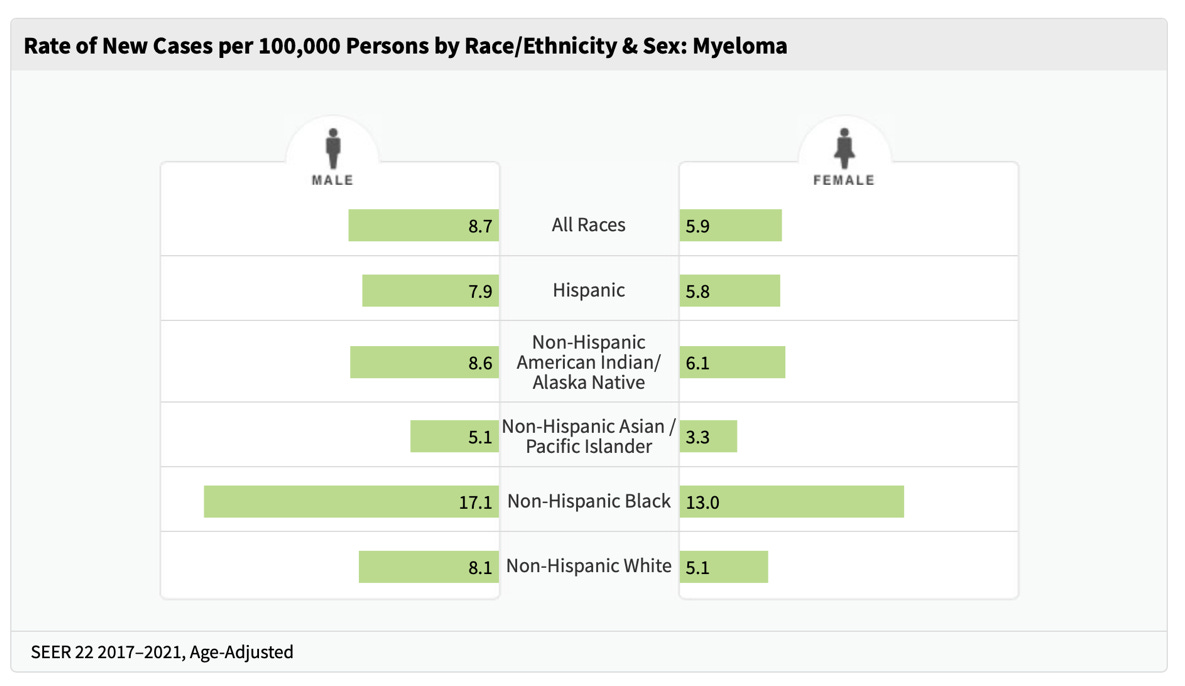

The final, must-see, chart breaks down gender and ethnicities of newly diagnosed myeloma patients in the population over a five-year period ending in 2021. Two things stand out. First, men are more likely to be diagnosed than women. Second, Blacks are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed as compared to every other category listed, with men having the highest risk.

Looking at this chart immediately negates any notion of racial disparities in cancer as irrelevant. They obviously are. While the numbers have increased at generally the same rates for the past three decades, little-to-nothing has been done to actually close the statistical gaps.

True, awareness has grown significantly in the past few years. Advocacy organizations climb over each other to claim more credit with outreach programs targeting Black patients. Pharmaceutical companies have made Black participation in clinical trials a key corporate goal. But other than public relations, not much has translated into clinical care yet. If they eventually do, the results should be seen in future NCI SEER myeloma pages.

The lack of substantive improvement in racial disparities will, I hope, at least cause some researchers to be nudged to consider diversity medicine. If, for example, theories that something in Black genetics causes higher incidence and death rates in myeloma are true, just how exactly are Black genetics measured and standardized to be compared fairly in randomized studies? And can other, non-genetic factors be standardized to incorporate them into existing standards or create new ones?

NCI SEER doesn’t provide answers, but it’s numbers potentially prompt uncountable questions.

One problem with statistics is numbers are expressed mostly in the abstract. What do these numbers look like at all in everyday experience? How can these numbers be better visualized and put into the context of an individual? The answer can be found in comparing them to metropolitan statistical areas (MSA) and linking their numbers to myeloma incidence and mortality figures, which provides a more accurate picture of myeloma than NCI SEER data alone.

In an MSA of five million people, like Boston, that would translate into about 350 annual diagnoses and more than 3,100 people living with myeloma at any given time. As a former colleague of mine would often say about myeloma, “it’s a rare disease, but hardly uncommon.”

But it’s not all improving news. Patients diagnosed with high-risk disease, which is now being refined into separate definitions of ultra-high-risk disease, still have significantly more obstacles in finding successful treatments and have lower survival rates. Additionally, Rafael Fonseca of the Mayo Clinic estimated that as many as eight percent of newly diagnosed myeloma patients don’t live long enough to make it to their first treatment.

Statistically speaking, the big picture is as good as it’s ever been and improving. For each individual myeloma patient, though, it depends.

[As I perused the list of the fifty largest statistical metropolitan areas in the United States, I subjectively identified forty-one as being within a reasonable distance to either a specialist or hematologist-oncologist with limited specialties including myeloma, including all the twenty largest. Twenty-five years ago, that number would have been less than ten, especially since Little Rock isn’t big enough to make the list.]

As much as I anticipate NCI SEER annual updates, I know I’ll be seeing old data. Statistics look back and provide information to estimate how things currently are. That’s the extent of how far into the future they “see.”

It takes time to compile, analyze, and publicize. Know, therefore, that when you see a press release or story citing some general myeloma statistic, the odds are they came from NCI SEER. And when they cite figures of 170,000 or 180,000 patients in the United States, you’ll know they’re citing old data, even though it’s the latest available.

If you’re an engineer, statistician, baseball fan, or just curious, the NCI SEER page contains links to more detailed and customizable data to keep you busy going down any number of statistical rabbit holes. That’s too much for most folks – and for me as well. Revisiting once a year for twenty minutes should do for almost everyone.

Try to understand and put into context, but don’t obsess.

I jumped the gun a bit in the conclusion to my last article. In my next piece, I’ll share some conclusions about what this and the previous three articles might reveal about patient education and advocacy, in the United States and throughout the world.