The Unknown Cost of Resistance

Concluding Our Tour of Berlin's Past

“Fascism is a cancer that spreads rapidly, and its return is threatening us: is it too much to ask that we oppose it from the start?”

~ Primo Levi, This Was Auschwitz

I know yesterday’s walk was physically and emotionally exhausting; I hope it wasn’t too much of an imposition to pack into one day. Each story taken alone could take countless hours and volumes to contemplate. But the themes are not unique. In every nation, every culture, every historical age, they are often repeated, in differing contexts. Berlin, in my opinion, provides condensed lessons about the universality of the constant tension between freedom and oppression.

We’ll spend today at the Plötzensee Memorial Center (Gedenkstätte Plötzensee), which is in a seemingly odd location: within the walls of a still-active prison. So it’s not easy to find and few tourists know about it. Much like the May 10, 1933 book burning memorial, you have to know where to look.

Remember to ask the cab to drop you off at the corner of Saatwinkler Damm and Huttigpfad – the corner of Plötzensee Prison. The driver may think you are mistaken about your destination. The first thing you’ll see will be the entrance, looking like a hospital emergency room entrance straight out of an old Kojak episode. I’ll be there waiting for you.

“The Weimar Republic did not fail because there were too many Nazis, but rather too few genuine, committed democrats…Too few Germans inwardly accepted the results of the first World War and the transition to the Weimar Republic…They let the people gradually lose belief that the Republic was in a position to defend against chaos.”

~ Richard von Weizsäcker, President of Federal Republic of Germany (1984-1994)[1]

We’re going to take a brief walk on the cobblestone street, Huttigpfad, with the high prison wall to our left. To our right, between us and one of Berlin’s many canals, is an industrial/warehouse zone, making our destination somewhat improbable. You’ll see our destination across from the small parking lot down the street, a small opening, the white strip interrupting the continuous red brick wall.

Catholics have the Vatican; Muslims, Mecca; Buddhists, Bodh Gayā; Jews, the Temple Mount; Hindus, Varanasi. Virtually every faith has pilgrimage sites – physical, tangible places where adherents connect with their deepest beliefs. I have Plötzensee.

You may think it a somewhat odd choice. But it is, for me, a deeply sacred place with a condensed lesson of opposing realities that are never as distant in our lives as we may want to believe. Plötzensee is a place of remembrance of atrocities of which man is capable, in the form of government policy, in ways that were once unimaginable. But they happened and we must remember. I’ll likely never visit places like Babi Yar, Choeung Ek in Cambodia, Santiago Chile’s National Stadium, Wounded Knee, South Dakota or most of the seeming innumerable sites of government-sanctioned atrocities. But I’ve been to Plötzensee, and I’m glad you can come along to share it with me.

Places like this are stark reminders of the ultimate costs individuals pay to resist them. They are shrines to the worst and best of humanity. Preserving them fulfills a need to contemplate man’s most inhuman acts, to not let them fade into oblivion. Remembering is essential for a free society to remain free. Forgetting is essential for oppression to thrive.

What distinguished Nazi racism was more the power to act on it than the values behind it.

~ Robert Wiebe, Who We Are: A History of Popular Nationalism

Usually a more common destination for people who want to see and experience tangible evidence of the horror of Nazi fascism is a concentration camp site. I’ve visited many over my lifetime. My first visit was to Dachau, just northwest of Munich, when I was eleven, and I’ve been there many times since. I’ve also visited Buchenwald, Bergen-Belson, Sachsenhausen, and Ravensbrück, a camp that only imprisoned women.

Dachau was the first concentration camp, established on March 22, 1933. It was, to use a Nazi euphemism, a “reeducation camp” for political prisoners – mostly communists, social democrats, and trade union leaders. Jews were not specifically targeted, but for those who ran the camps, it was a “bonus” when the categories overlapped, giving them more incentive to treat selected prisoners even worse, with complete, vicious impunity.

As I mentioned yesterday, although the terror had been planned for years, as outlined in Hitler’s book Mein Kampf, the Reichstag Fire on the night of February 27-28, 1933 was the trigger moment that set everything to come in motion. It began with the arrest of the most hated critics of Naziism, including Carl von Ossietzky. Among the arrested was Erich Mühsam, a poet, essayist, and playwright who founded a magazine in 1926, Fanal, that was the most vitriolic anti-Nazi publication of its time, arguably more intense than Ossietzky’s Die Weltbühne.

Mühsam, an influential Marxist anarchist intellectual, opposed Germany’s entry into World War I. Nazis later claimed he was an integral player in “Stab in the Back” conspiracism. He was asked to be a cabinet member of Bavaria’s six-day long Soviet Republic in 1919 and fought against a right-wing militia, the members of which formed the Nazi party soon after, in the chaos that ensued, resulting in a fifteen-year prison sentence handed down by a right-wing court. Released early after serving five years, Mühsam moved to Berlin to establish Fanal.

When he was arrested in the early morning of February 28, Mühsam was first sent to Plötzensee and later moved to various prisons. Soon after the Dachau camp opened, the first concentration camp in the Berlin region, roughly fifteen miles north of where we are now walking was established: Oranienburg. Mühsam was sent there and singled out for the worst treatment, often in front of other prisoners as a cautionary example.

His teeth were broken in repeated beatings. He was beaten into unconsciousness and revived with dousing of cold water in winter months, forced to dig his own grave and then live through clicks of unloaded guns to his head after, made to eat dirt, guards spit into his mouth, and subjected to daily, hourly humiliations, remaining defiant throughout. He was murdered by guards, led by the founding director of Dachau, who hanged his body and lied that he died by suicide, on the night of July 9-10, 1934. There were countless, similar fates, many of which are unknown to this day.

I can see how, with enough false education, enough widespread illusion and error, men can, while remaining men, believe this and commit the most unspeakable crimes.

~ Isaiah Berlin, The Power of Ideas

Existing concentration camps expanded and new ones were built in the newly conquered territories in eastern Europe after the Final Solution was planned and initiated at the Wannsee Conference, which took place just a few miles southwest of Plötzensee on January 20, 1942. (As you will recall, Roland Freisler, the architect and chief judge of the Volksgerichtshof was one of the attendees.) By this time, a majority of German Jews had already been eliminated – shot in Rumbala forest south of Riga, Latvia, sent to existing camps and jails, forced into ghettos in eastern Europe, and a relative few were able to escape and emigrate to Palestine and other nations around the world. The U.S. mostly restricted their entry.[2]

Those who avoided extermination and deportation, usually through marriages to non-Jews, were slowly restricted from employment and public places before being deported. One, Victor Klemperer, survived and kept diaries providing among the most detailed accounts of everyday life in Nazi Germany. He hid the diaries and retrieved them after the war. They are essential reading to get a full understanding of the Third Reich.[3]

In early 1942, he described how friends and acquaintances died by suicide after repeated harassment and threats of being sent to concentration camps which “is now evidently identical with a death sentence.” It was proof, although details were unknown to most, there was widespread knowledge of Nazi atrocities throughout Germany.

One of the moments of my life that still stands out was my visit to the Bergen-Belsen camp, located between Hannover and Hamburg. It was here that Anne Frank and her sister died, most likely due to typhus, after they were found and deported from Amsterdam.

I arrived late on a February afternoon, an hour before the museum closed (the most informative and touching of all the camp museums I have visited). After going through the museum, I was on the grounds, alone as the sun was setting on the cold winter day. Walking among the numerous mounds, indicating the burials of 5,000 here, 1,000 there, I got a stark, personal reminder of both the costs and the experiences those who lived and died there experienced.

The memories of those visits are what make Plötzensee so important to me. Here is where thousands who tried to publicize and prevent these tragedies were executed.

“…nonterrorists were also capable of atrocities, Auschwitz, for instance, was not the work of terrorists but of state employees…”

~ Friedrich Dürrenmatt, The Assignment

Now that we’ve reached the entrance of the Plötzensee Memorial Center, please let me take a little time to describe it. As you can see, it’s a small area, like a keyhole carved out of the prison grounds. We’re reminded that there really is still a prison on the other side by coiled razor wire on the top of the surrounding walls. To our right is an urn which contains handfuls of dirt taken from every concentration camp and their satellite camps from the Third Reich, with the inscription, “Dedicated in honorable remembrance to the victims of the concentration camps.”[4]

The original execution site has been reduced from four garage-like rooms to two, the remaining rooms are behind the wall in the center of the site, which bears the inscription The Victims of the Hitler Dictatorship in the Years 1933-1945. The open courtyard is the site of annual July 20 commemorations. Led by the President of Germany and include elected officials and cabinet ministers, it is a reminder that this site was once legally sanctioned, as much a function of government then as the ones they are responsible for now. The events are closed by ecumenical services at a nearby church with artwork commemorating the injustice that took place here.

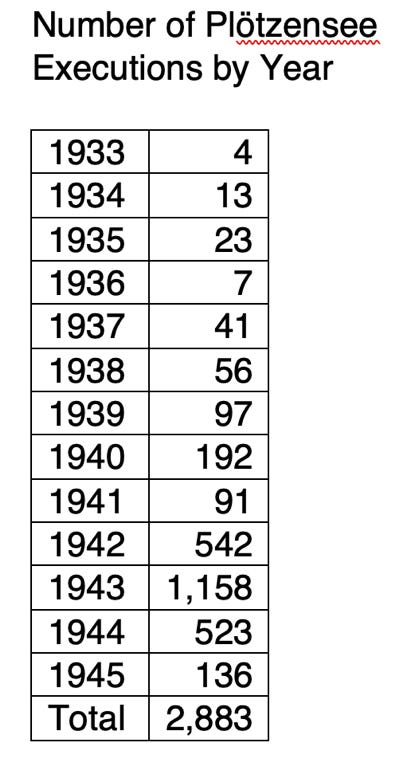

In addition to Germans implicated in resistance activities, some captured leaders of partisan resistance in other nations were also brought to Plötzensee for execution. Of the documented 2,883 executions that took place, 1,449 were German, 667 were Czech, 248 were Poles, 245 were French, 89 were Austrians, 64 were Belgian, and 35 were Dutch. The others executed represented fourteen different nationalities.

Guillotining was the most common method used by Plötzensee executioners, who were mostly drawn from the butcher profession. They had intervals of three minutes to conduct an execution, but with practice, they actually could do so in seven-to-nine seconds. Victims were strapped onto a board while standing, the board was flipped ninety degrees and the blade came down quickly. Among the “skills” of an executioner was the ability to correctly estimate the height of the person to be executed so that the neck could be put in the proper position without wasting time. Women had their hair cut short, above the neck.[5]

Many of the members of the July 20 plot were hung from piano wire attached to meat hooks to extend their suffering. Their executions were filmed because Hitler intended to use them for propaganda purposes. Of the two remaining rooms of the small building behind the wall at the center of the Memorial Center, one is preserved as an execution room, with the meat hooks on one end. The other room has an exhibition about the victims, including a searchable database and screens to pull up any story. I’d like to briefly share three of them.

The right? Ah, what does it help to be in the right if you don’t have any power?

~ Henrik Ibsen, An Enemy of the People

Elise and Otto Hampel, a married couple from Berlin, had never been politically active or vocal at any time. Upon learning Elise’s brother, a soldier, had been killed in battle in August 1940, just under a year after Germany invaded Poland, they undertook a secretive campaign to resist and inform people in Berlin.

For the next two years, the Hampels wrote anti-Hitler slogans on postcards and secretly placed them in mailboxes, phone booths, on busses and trams, and apartment stairwells mostly around the Berlin Wedding (VAY-ding) neighborhood. Unfortunately, the Hampels’ resistance didn’t have the effect for which they had hoped. Most people who found them, whether out of loyalty to or fear of the Nazi government, turned in 287 of the cards to the Gestapo, which set up a task force to locate the writers.

German author Hans Fallada[6] received a copy of the Hampels’ Gestapo file after the war. In 1947 he wrote the novel Jeder stirbt für sich allein (Every Man Dies Alone) in twenty-four days, and died shortly after, before an edited version was published. It was moderately successful. An unedited version was translated into English in 2009, becoming a huge sensation in the United Kingdom and in the United States, the latter due in large part to a glowing New York Times book review. The book had a renaissance in Germany as well and a movie, Alone in Berlin, was released in 2016.

Fallada’s book added fictional elements drawn from many of his personal observations, providing an insight into everyday life that matches well with Klemperer’s diaries. And he changed the names of the Hampels to the Quangels and Elise’s fallen brother became the Quangels’ only son, but otherwise, the details of how they went about their resistance activities and how the Gestapo eventually found them are very close to actual events.

The Gestapo task force created a map – which is depicted on the inside cover of the novel – to show where every reported postcard was found. Before the Hampels were identified, the Gestapo had narrowed down the home of the postcard writers to the exact street and, by matching the locations of cards found outside of the Wedding neighborhood, determined the likely location of Otto’s workplace and were able to piece together the rest of the story.

The Hampels were tried before the Volksgericht, with Roland Freisler presiding. They were executed at Plötzensee on April 8, 1943.

Mildred Fish-Harnack,[7] from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was the only American to be executed at Plötzensee. In 1925, she met Arvid Harnack, a German studying at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she was a graduate student. They married the next year and by 1929 both were living in Berlin, with Arvid working as an attorney for the economic ministry and Mildred furthering her education in German to prepare for a teaching career.

They traveled together to the Soviet Union in 1932, where Arvid was sent to learn about agricultural reforms and Mildred was impressed with the relative equality of women. After Hitler became chancellor, they resisted joining the Nazi party and became close friends with Harro Schulze-Boysen, who, in 1934, was a lieutenant in the German air force intelligence division, his wife Libertas, was a press agent for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Both couples opposed the rise of Naziism and soon engaged in resistance activities together.

Early on, they were supplied by the Soviet Union with broadcasting equipment to share information and engage with other like-minded, left-wing opponents to Hitler and the Nazis. Their jobs also gave them opportunities to travel on business to the United States and the Soviet Union before the war.

Over time, the Gestapo began intercepting messages, which included information about Germany’s agricultural, industrial, and military capacity, naming the network the Red Orchestra (die Rote Kapelle), a term they never used but became most associated with them. It is estimated that the group had as many as 150 members, some as far away as Brussels, Belgium, all in communication with Moscow.

Their work began to be compromised when Hitler and Stalin signed a pact in 1939. Not only were they betrayed by the spirit of the agreement, subsequent documents revealed after the fall of the Soviet Union proved that the nation turned over German and Austrian dissidents as well as Jewish refugees to the Nazis. Between August 1942-March 1943, at least 126 members of the resistance group were arrested, including the Schulze-Boysens and the Harnacks.

Arvid was found guilty of treason and was executed by piano wire hanging at Plötzensee on December 22, 1942. Mildred was also tried and given a six-year sentence, but Hitler personally intervened, ordered a new trial that sentenced her to death. She was beheaded at Plötzensee on February 16, 1943. Reportedly her last words were, “And I have loved Germany so much.”

Because of the Cold War, the resistance of the Harnacks and their group were belittled or even ignored in the West. Wisconsin senator Joe McCarthy hated them and blocked any recognition of them, which held until the mid-1990s. In the eastern bloc, especially in the former East Germany, the Red Orchestra was lionized while the July 20 plotters were diminished as tools of capitalism. Unfortunately, neither group was aware of the other while they were active, ultimately diminishing their potential to fight Naziism.

Adam von Trott du Solz was a member of Kreisau Circle (die Kreisauer Kreis). Born into a family of minor nobility, he was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University from 1932-1933 when Hitler became chancellor. Although opposed to the Nazi government, he returned to Germany. He received a law degree earned a stipend to study and live in China for a year in 1937-1938.

Trott joined the foreign ministry in 1940 after becoming a member of the Nazi party, a prerequisite to get a top job. By then he had become close to Helmuth James von Moltke, the leader of the Kreisau Circle, met often with leaders of the military resistance, and became an important connection between the two leading up to the July 20 plot. Because of his high-ranking position, he was one of the few Germans who could leave the country on diplomatic missions.

As he tried to make connections with American and British leaders, his attempts to were rebuffed because neither nation was open to negotiations and distrusted his motives. Both Roosevelt and Churchill maintained a commitment to unconditional surrender when it came to Germany; there would be no cooperation, formal or informal. Trott also traveled often to Sweden, which was neutral in the war, making connections with German exiles including Willy Brandt, the future mayor of West Berlin and chancellor of West Germany.

Had the July 20 assassination of Hitler succeeded and installed a new government, Trott was designated to be its foreign minister. Instead, when it failed, Trott was arrested in his office five days later, tried before Freisler’s Volksgerichtshof, and executed at Plötzensee on August 26, 1944.

Since we’ve spent the last two days learning about some of the consequences of Nazi dictatorship, I thought it would be good to have something of an uplifting conclusion in the story of Harald Poelchau (POE-el-sch-ow), who was the pastor at Plötzensee Prison as well as Tegel (Tay-ghel) Prison, two miles to the north, and Moabit Prison, which held female prisoners, from 1933-1945.

Poelchau was a pastor’s son who grew up in Silesia and studied theology under Paul Tillich, who founded religious socialism and was later one of the strongest intellectual influences of Martin Luther King, Jr. Much like his friend Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the founder of the Confessing Church, Poelchau believed in ministering to “people on the edges of society” and was skeptical of the modern state because of its “tendency to lose its humane orientation.”

Upon graduating from theology school, he decided to work in the prisons because it was the only religious position left in Germany that was not subject to Gleichschaltung. He had been strongly influenced by the Bible verses Matthew 25:36 (“I was in prison, and ye came unto me”), 25:39, and 25:44, which all referred to visiting those in prison. He became a member of the Kreisau Circle and likely had more connections to other individuals and groups involved in resistance to Hitler than anyone.

As persecutions and death sentences rose, an important part of his ministry included spending the final hours with those condemned to die. Poelchau accompanied more than 1,000 people to their executions, many who were close friends from the resistance, often spending the last evenings with condemned prisoners, helping them to write their final letters and personally delivered them to their loved ones.

Together with his wife Dorothee, Poelchau protected countless people outside of the prisons; harboring individuals and families, securing illegal employment, providing access to false papers to hide identities, finding other people to provide shelter and cover alibis. He helped Jews, evangelicals, atheists, soldiers, children—in other words, anyone who needed help, all the while maintaining his anonymity.

Poelchau often requested persecuted people who needed help to visit his prison offices, correctly reasoning that no authority would suspect such brazen acts would occur right under their noses. The Tegel prison cook, Willi Kranz, was convinced by Poelchau to hide a young Jewish girl for a year. He strongly believed his obligations included seeing to the needs of dependents of those executed, who were almost all arrested and separated from their children, as he did for the widow of his good friend Trott.

Poelchau befriended and ministered many captured freedom fighters from other nations who were brought to Berlin to be executed. After the war, he was often the only German invited to speak at memorial services in the Netherlands, Norway, and England. Just a few months before his death in 1972, he and Dorothee were honored at Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust memorial and historic research center, as Righteous Among the Nations.

After the war, Poelchau worked in a religious social welfare agency, briefly went back to work at a Berlin prison under Soviet command, and eventually became a social pastor. He had no church but focused on pastoring to workers and union members in small groups. They often met at his kitchen table or their workplaces. His idea of a ministry was not formal, it was meant to be among factory workers, laborers, and other members of the working class.

His story is arguably the only positive one to emerge from the horror of Plötzensee.

Totalitarian solutions may well survive the fall of totalitarian regimes in the form of strong temptations which will come up whenever it seems impossible to alleviate political, social, or economic misery in a manner worthy of man.

~ Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

This brings our tour of Berlin to an end. You should take some time to experience other parts of the city. It is no longer a place of persecution; it may well be the most progressive city in the world today.

The real lesson of our time together, I think, is that we can’t understand the value and worth of democracy and individual rights until we lose them. Once lost, it is impossible to predict the consequences that will come. And they will always be worse and more tragic than anyone could ever have predicted or envisioned.

Never has Democracy reacted as promptly as when it came to doing nothing against dictatorship.

~ Kurt Tucholsky, Briefe aus dem Schweigen: 1932-1935 [8]

[1] „Die Weimarer Republik ist nicht gescheitert, weil es zu viele Nazis gegeben hatte, sondern zu wenig wirklich überzeugte Demokraten…Zu wenige Deutsche waren es gewesen, die den Ausgang des Ersten Weltkrieges und den Übergang zur Weimarer Republik innerlich angenommen hatten…Sie ließen die Menschen allmählich den Glauben verlieren, daß die Republik imstande sei, einem Chaos zu wehren.”

Weizsäcker’s father, Ernst von Weizsäcker, was a leader of a planned 1938 assassination of Hitler, along with Ludwig Beck, that was called off after British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain negotiated his “peace in our time” treaty ceding the Sudetenland to Hitler. He served in the foreign ministry from 1938-1943 and as German ambassador to the Vatican from 1943-1945. He aided the July 20 plot but was convicted of crimes by a war tribunal in 1949, a sentence Winston Churchill called “a deadly error.” Weizsäcker’s brother, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, was a prominent physicist who was credited with helping to slow down Nazi atomic bomb research during the war.

[2] David S. Wyman’s The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941-1945 (Pantheon, 1984) is a thorough discussion of this history.

[3] Klemperer wrote: “Eva [his wife] does not like to hear me talking about Hitler; I myself am as intensively concerned with him as a cancer researcher is with cancer.” After Jews were prohibited from going to libraries, he started writing LTI: lingua tertii imperii – The Language of the Third Reich, a collection of essays examining the language of Nazi propaganda. One of his key observations: “…the basic principle of the whole language of the Third Reich became apparent to me: a bad conscience; its triad: defending oneself, praising oneself, accusing—never a moment of calm testimony.” He was scheduled to be transported to an extermination camp in 1945, but was saved when his native Dresden was fire-bombed. He and his wife joined the mass of refugees moving south, away from invading Russians and toward invading American. Near the conclusion of his diaries, he recounts a conversation with a woman who claimed, “Liberalism is to blame for everything bad.” To which he responded, “I must explain to her: A liberal is someone who stands by the sentence: In my father's house there many rooms. A scholar who does not agree with that sentence is no scholar.”

[4] „Den Opfern der Konzentrationslager in ehrendem Andenken gewidmet.“

[5] These details are summarized from the memoir of Harald Poelchau, the prison pastor who will be discussed below.

[6] Fallada was the pen name of Rudolf Ditzen, a man with a troubled personal past that included suicide attempts, was an alcoholic and drug addict with an exceptional storytelling gift. Unlike many authors who went into exile during the Nazi era, he went into “inner emigration,” staying completely out of politics to remain in the country to write nonpolitical novels, which were still heavily censored, sold very well, and are still in print. Another author who chose inner emigration, Erich Kästner, was the only author to see his books burned at the Berlin rally on May 10, 1933. His choice to stay was deliberate, to bear witness, survive, and tell the world what life was like under Naziism when the war ended. He earned money by writing children’s books and fables. His book Emil and the Detectives (Emil und die Detektive) is still a staple of German language instruction in the United States and around the world.

[7] Shareen Blair Brysac’s book Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and The Red Orchestra (Oxford University Press, 2000) is the most comprehensive English-language book available on this subject.

[8] „Noch nie hat die Demokratie so prompt reagiert, wie wenn es sich darum handelt, etwas gegen die Diktatur nichts zu tun.“