Robert Kyle wasn’t born in a log cabin, but it sure seemed plausible to anyone who ever knew him; there was something Lincolnesque about him. Sincere, thorough, respectful, patient, studied, direct, and beguilingly humble. He lacked Lincoln’s poetry and sense of humor, but not a genuine appreciation for it.

Or perhaps he was closer to a Washington who, like Kyle, didn’t need similes or metaphors to grace his papers with simple, straightforward elegance. The facts spoke for themselves. As they have for Kyle’s whole life.

His parents never made it past eighth grade, not out of the ordinary in pre-depression era Bottineau, North Dakota. Located twelve miles south of the Canadian border and almost directly between the east and west state lines, its flat, fertile prairie was home to an impressive 700-acre farm centered around a solid, no frills, functional two-story white house in which five sons were raised to expect to work hard, both on the farm and as adults.

Security of family and community provided the Kyles with support during hard times, which thankfully were few and far between for a family in the depression/World War II era. Even those few produced indelible memories Kyle would recall eight decades later. The Kyle farm would be one of many supplying grains to a growing nation that contributed immensely to making the 20th century known as an “American” one.

Together with his four younger brothers, Kyle had an upbringing much like most in 1930s rural North Dakota. Work came first, education was essential. Both required never-ending, diligent effort. Kindergarten through eighth grade was in a one room schoolhouse near the Kyle farm. He loved riding his Welsh pony to get there.

Kyle’s eager intellect stood out from the beginning. It was practical. When asked by a teacher to take a test to skip seventh grade, he figured he did well enough, but decided to stay with his class anyway. He was in no rush.

There was a lot to keep him interested and learning. High school in Bottineau meant rooming with another student during each of the four school years. The six miles back-and-forth to home would cut into school time, especially in North Dakota winters. After high school, Kyle started out as a forestry student in a junior college.

Surely it seemed impossible to imagine what kind of future awaited him when he graduated from Bottineau High School and went on to the town’s University of North Dakota’s School of Forestry for the next two years. He would spend summers alone, high up on a stand, overlooking trees and collecting data. It was interesting being out in nature, but impatient curiosity and talent led him on to Grand Forks and the University of North Dakota Medical School.

The dean recognized something special in him – much like his one-room schoolhouse teacher – encouraging Kyle to attend his alma mater, Chicago’s Northwestern University, to attend a more demanding medical school. He excelled again, studying up to six days a week from when he woke up to his 10 pm bedtime. From there it would be on to the Mayo Clinic for a three-year internal medicine fellowship.

Instead, Cold War geopolitics unexpectantly intruded on his life, as it had for young doctors throughout the nation in 1952.

The “Doctor Draft” required graduating medical school physicians to serve in the military for two years. Additionally, virtually all medical residency programs only accepted candidates who had completed their service, creating incentives for those who wanted to specialize in a field of medicine to get it over with as soon as possible. Kyle put his studies at Mayo on pause.

“Obligated volunteers” who already had medical specialties had better chances for plum assignments. Kyle didn’t have one yet, and first got news he would be sent overseas to Turkey. His wife Charlene would not be able to go with him, but once again, fate smiled on him.

Assigned to Anchorage, Alaska’s Elmendorf Air Force base instead, Kyle joined 10,000 soldiers plus their dependents at its 400 bed military hospital. He stayed for the next two years – with Charlene. It was a great place to be for a former forestry student figuring out where he wanted to go in life.

Kyle became something of a mid-20th century country doctor, treating everything and anything that came through the front door of the hospital. After returning to Mayo the idea of reading smears lost its luster. Based on his experiences in Alaska, solving the riddles of clinical hematology seemed much more fulfilling than reading blood smears.

One of the new diagnostic tools still in its infancy intrigued him: electrophoresis, a process applying electrical charges blood samples to identify, separate, and measure blood serum components that could be represented on graphic charts. Blood serum is made up of proteins, a subset of plasma, but without the clotting factors needed to repair scraps and scratches.

In reading some graphs, Kyle saw similar M-like patterns he couldn’t explain. The left side of the M-like pattern represented albumin, the most prevalent, and subsequently, the easiest protein to find. The right side represented high levels of gamma globulin, another protein in blood. In a normal readout, it would be low, looking more like a downhill slope, rather than rising abruptly.

After returning to Mayo when his service was finished, a colleague suggested he investigate it because it seemed to have a correlation to myeloma and macroglobulinemia, an even rarer type of cancer of uncontrolled multiplying of white blood cells. Sifting through more than 6,000 individual readouts from the previous three years of Mayo patients, Kyle indeed saw those patterns correlate to myeloma plus another rare one that was unfamiliar to him.

AL amyloidosis, not technically a cancer, was a hematological disease that mutated certain proteins, causing them to attack organs like the heart and other tissues. After looking the 80 readouts of the amyloidosis patients again, he realized that many of them were misdiagnosed and actually had myeloma. Research would later confirm that a certain number of patients would be diagnosed with both diseases at the same time. “From that point on,” Kyle would later recall, “I was set on working in the area of myeloma, macroglobulinemia, and amyloidosis.”

Kyle’s research was published in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), a rare feat for a young doctor’s first paper. In later years, as treatments led to longer lives, the absence of the M spike, or the M protein, was confirmation of remission.

For the next five decades-plus, Kyle would define and give order to the fundamental vocabulary of myeloma, amyloidosis, and other hematological diseases. The emergence of myeloma as a distinct discipline would not have been possible without him.

But first, Kyle would have to get his training and credentials to become a specialist. As much as Mayo offered Kyle, he needed more than it could provide. He had to move on before moving forward. Finding the right mentor mattered. And that person was in Boston.

I’ll get back to more of Dr. Kyle’s story in a couple of weeks. First, a slight detour, beginning on Friday, April 26, instead of the normal Sunday post.

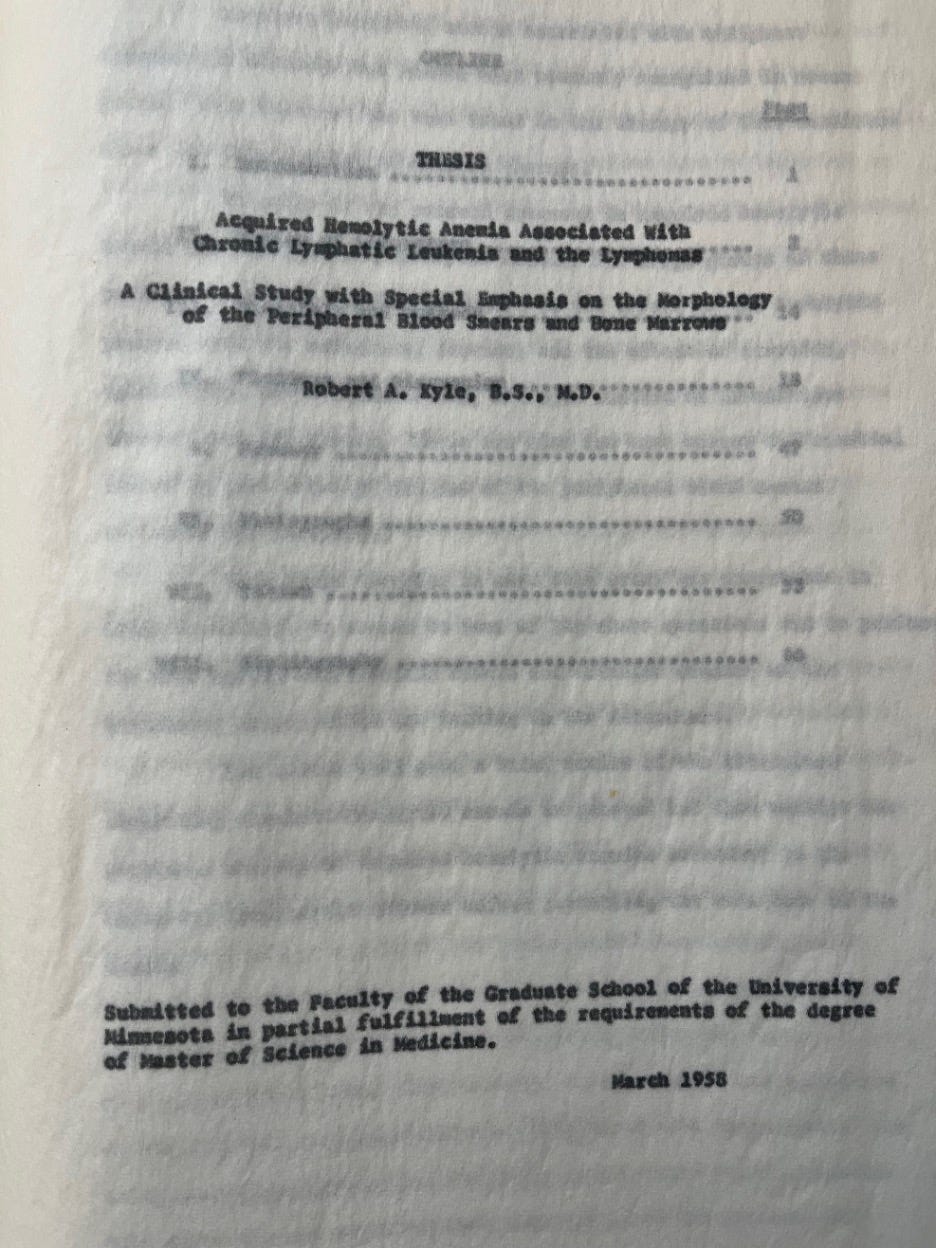

Photos: Dr. Kyle sightseeing on bridge over the Neckar River in Heidelberg, Germany (ca. 2009); cover page of Dr. Kyle’s Master’s thesis.

Fascinating Greg. Will you eventually publish a book???