In Defense of the Scientific Method

Democracy’s Rosetta Stone?

The method of scientific investigation is nothing but the expression of the necessary mode of working of the human mind.

To paraphrase Yogi Berra, it seems like déjà vu all over again. The deluge coming out of the White House, with random issues constantly whizzing by, makes it seemingly impossible to concentrate on any one at all. That’s a big part of the plan.

Contrived antagonisms with friends including Canada, Mexico, Panama, Denmark, Greenland and the European Union, threats to abandon Ukraine unless “we” (whoever that is) get their “rare earth,” embracing virulent anti-democratic despots, closing federal agencies without any authority to do so with an agency that has never been authorized to exist, and withdrawing from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Paris Climate Accords is just a beginning. And last night we learned the U.S. is supposed to be the new owner/operator of a planned Coney Island/Atlantic City on the Mediterranean, once known as Gaza.

United States’ policy now shuns multilateral alliances that do not put it and its leadership’s perceived interests at the top of every hierarchy, real or imagined. Everything ranging from constitutional law to expected functions of government are rapidly becoming contractual. And bilateral. Negotiable, one-on-one agreements in which the American side can be publicly characterized as “winning” will be the standard for success. Even things that have been considered inalienable rights will be up for grabs.

Taken together, these policies obliterate carefully evolving concepts like checks and balances and separation of powers, which are the oil and machinery that make this democratic-republic run. But there’s even something more basic at stake, something we all learned in elementary school: the scientific method itself.

In my view, the scientific method is the Rosetta Stone of democracy itself, without it there is no order, no way to translate its meaning, nor make sense of what everyone sees and experiences. There is a danger of both ignoring or inferring the wrong lessons and misinterpreting what they tell us. That’s why it’s important to ask what those lessons are and why they matter. Now more than ever.

From the ancient Egyptians through the advent of the 20th century, the idea that diseases were caused by imbalances in the body was more or less a given for those who treated them. This mindset’s apex was reached just as the Medieval Age was ending around the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries: the belief that good health was dependent on the balance of the four cardinal humors – blood, phlegm, choler, and melancholy.

This belief lingered in some ways as late as the latter part of the 19th century, when bloodletting and leeches were still occasionally applied to treat diseases. Around the same time, the best “physicians” in the world were sticking their unwashed fingers directly in President James Garfield’s wounds and ensuring his eventual death, either unaware or dismissive of Joseph Lister’s research on antiseptics.

Just more than 600 years ago, Francis Bacon articulated the scientific method based on facts, observable phenomena, and systematic reevaluation, arguably the Enlightenment’s first and most important legacy. Thomas Henry Huxley, a British biologist/natural historian and contemporary of Charles Darwin, went so far as to call it common sense.

The scientific method is a way of building knowledge, assembling ideas into constructs of all types, physical and intellectual, lessons to learn and on which to act. I would argue it is the most important. One idea can’t be confirmed without the verification of an earlier one.

I was reminded of this whenever I was in my hometown, where every day I walked by where Karl Landsteiner, who identified the three known human blood groups and received a Nobel Prize in 1901, once lived when he was a university chemistry student. To me, it was a constant reminder of the relativity of knowledge and how it was dependent on time. Any medical school graduate today knows vastly more than he could ever imagine when he was their age.

The single most significant reason for this progress can be found in applications of the scientific method, which must be appreciated in order to survive. This means understanding and accepting that one might be proven wrong; it might even clash with chosen beliefs that either cannot apply a scientific method or ignore it altogether.

Huxley coined the term agnostic to underscore the central role of empiricism in the scientific method, to separate science from theology. It might reveal error which, regardless of history or culture, has been popularly determined to be divine. Every founding story or myth is grounded in some religious idea.

Countless philosophers and, increasingly in the past century-plus, social scientists have tried to explain this logically. In the 19th century, for example, Max Weber linked a protestant work ethic to the economic underpinnings of capitalism and human behavior. He took the unquantifiable and subjective concept of faith, mixed in a healthy dose of empiricism based on his own criteria, and gave it an aura of scholarly legitimacy to influence generations of western political and social life.

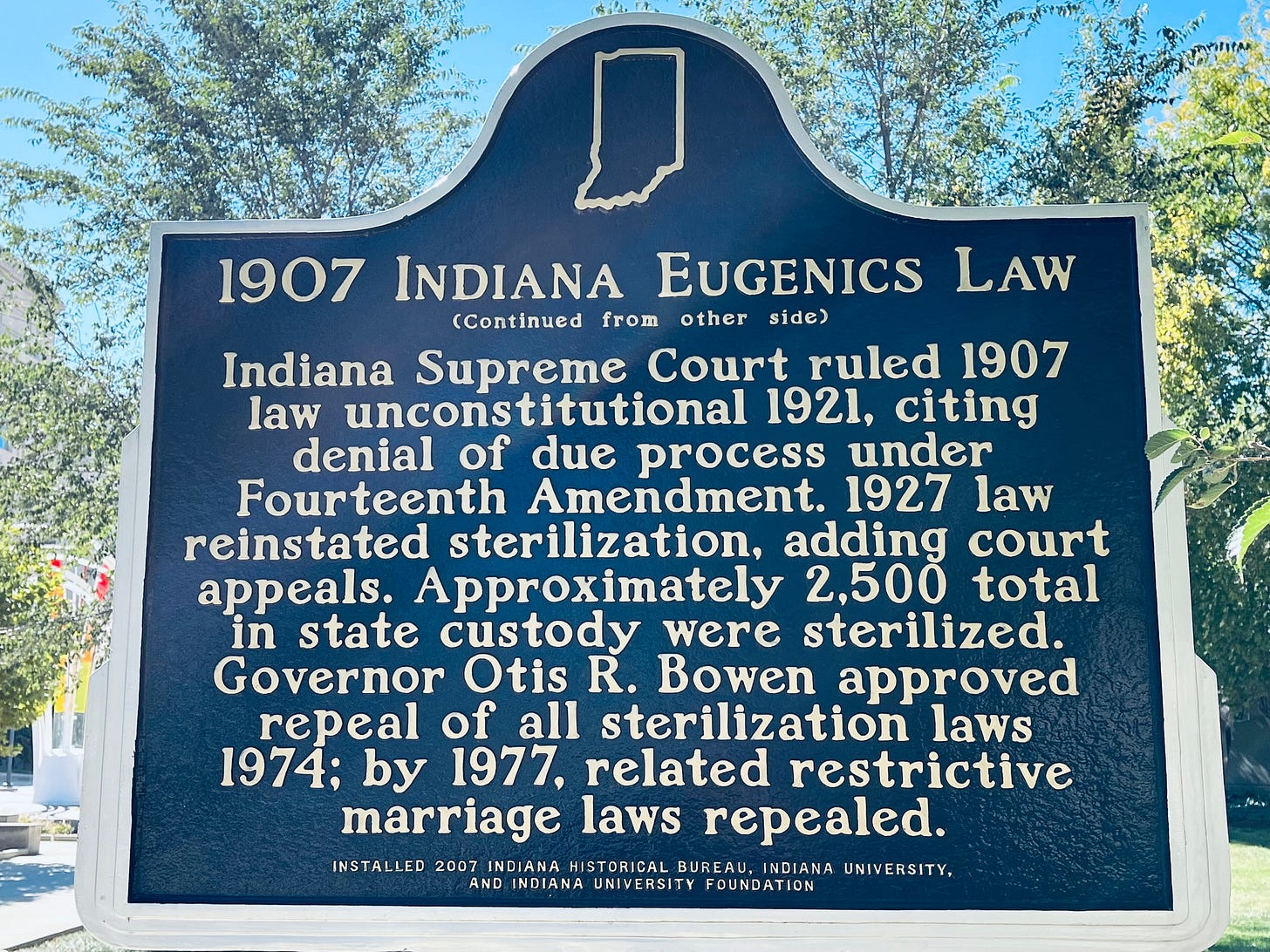

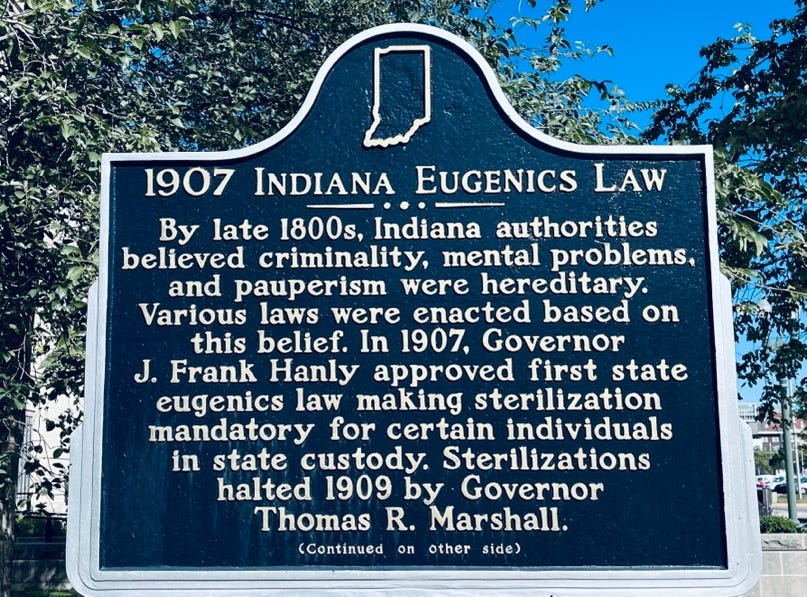

On the other hand, so-called scientific “methods” were twisted to create crackpot ideas like social Darwinism, which claimed to rank humans “scientifically,” making some “superior” to “more useful or productive” than others. It became the basis for the quack science of eugenics, which found its first ever legal justification in a 1907 Indiana law, and eventually gave a central organizing goal to Naziism.

The “science” of eugenics merged with the conspiracisms[2] surrounding The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a virulently anti-Semitic fiction invented in late 19th century Russia. The Protocols were taken as fact by mostly far-to-extreme-Right that emerged out of the end of World War I. Indeed, they still are among far Right political movements in the United States. Henry Ford, one of the richest men of his, or any, time, paid to translate The Protocols into English and distribute them throughout the nation in the early 1920s.

In Germany, the “science” of eugenics merged with the conspiracisms of The Protocols combined with the lie of “stab-in-the-back” that “led” to Germany’s World War I defeat, creating enduring political instability for the Weimar Republic, leading to the Nazi takeover of power in 1933. This central fiction became the basis for creating a parallel legal system of political courts called the Volksgerichtshof, which I discussed on our tour of Berlin.

A scapegoat, if we must identify just one ultimate culprit (despite slavery having existed long before he was born), is perhaps Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist from the 18th century.[3] He was not particularly well-educated, but his tenacious ambition and marketing skills led to his lasting impact on modern science.

Linnaeus was, according to Roberts, a “pious” man who “believed all of life was exactly as God created it” and “figured there couldn’t be more than 30-40,000 species in the world.” Although he would claim a method, he was both arbitrary and influential in classifying life, geology, and history, in “trying to put order where none was” to “justify the idea that there was a static universe.” Buffon, although he might not have described it as such, was much more methodical, scientific, and deferred to local cultural names and descriptions in organizing.

Over time the Linnean viewpoint grew to be more accepted. One reason was because it reinforced existing views and prejudices. According to Roberts, Linnaeus’s impact “became almost a form of colonial colonization. It was a huge appeal, in the early Victorian era, to be able to go and absolutely ignore any such thing as indigenous names or any local information and basically just award the naming rights to the person who ‘discovered’ it.” Moreover, it was great marketing that appealed to fame and vanity.

When Linnaeus got around to man, homo sapiens, he “identified” four sub-species that were arbitrarily linked to the colors of the four cardinal humors – blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile – which he classified as Americanus, Europaeus, Asiaticus, and Africanus. He listed five categories of personal, completely arbitrary distinctions, to classify them, skin color, physical traits, behavior, clothing type, and government summarizing them as:

I won’t spend any time analyzing the chart above. Instead I encourage readers to go over it slowly a few times, taking time to consider the words’ long-term implications, consider how they have seeped into public opinion, decision-making and laws. The words buttress grave historical misconceptions; they speak for themselves. They still drown out the scientific fact that we are biologically 99.9% the same for political reasons.

Linnaeus simplified based on personal preconceptions. His definitions of race have too often been cited as “scientific” rather than what they are: social constructs created by fallible humans. These misconceptions and lies are still central political arguments, many of which are currently ascendant in the United States and spreading throughout the world.

Another unlikely scientist showed the way at the end of the 20th century. His views are worth resurrecting.

A student comes home after school: “We solved a difficult math problem today: 7 x 8 = 54.” – “But it’s supposed to be 56!” – “That’s what our teacher said, but the majority of class said it was 54.”

~ An old joke

Carl Sagan might seem like the unlikeliest of authorities to assess the state of governing today. An astronomer who taught at the best universities in the 1950s and 60s, Sagan was the most recognizable American scientist of his time, due in large part to his popularly accessible, award-winning books and hosting of the Public Broadcasting series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage in 1980-1.

Sagan spread himself thin into fields beyond astronomy, believing he had a responsibility to make science understood by average people and inspire. He was easy to underestimate because his popularity, distinct speaking style and comical interpretations of him. He wrote his final book with the awareness that he might soon die of cancer.[4] Published in 1996, it was his testament, a warning and plea about the scientific method’s essential role in democracy: you can’t have one without the other. He was one heck of a diagnostician.

“Science,” as Sagan emphasized in his final interview, “is a way of thinking.” It “invites us to let the facts in, even when they don’t conform to our preconceptions.” In connecting the scientific method to democracy in the book’s final chapter, “Real Patriots Ask Questions,” he also expressed his greatest fear:

We can be manipulated into utter senselessness by clever politicians. Give us the right kind of leader and, like the most suggestible subjects of the hypnotherapists, we’ll gladly do just about anything he wants – even things we know to be wrong. The framers of the Constitution were students of history. In recognition of the human condition, they sought to invent a means that would keep us free in spite of ourselves.

Sagan pays particular homage to Thomas Jefferson – a founder and not technically a framer. Despite aggressive efforts to rewrite Jefferson’s history and pin ideas to him he did not hold, he long recognized a deep, fundamental link between the scientific method and the achievement of, as he wrote in the Declaration of Independence, “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Sagan goes on to quote a historian/colleague to emphasize his conclusion, “Science and its philosophical corollaries were perhaps the most important intellectual force shaping the destiny of eighteenth-century America.”

Reading those words still triggers the civic educator in me. You see, there is a myth about citizenship in a democratic-republic: Citizens don’t, despite the rhetoric used by all sides of the political spectrum, “participate” in government in any way. Citizens monitor and influence – or at least, they try to – with summary conclusions made at the ballot box, hopefully.

A very few might occasionally write their federal, state, or local representatives. Even fewer actually take time to become personally engaged is some way. Indeed, if Jefferson had his way, he would have included a ward system in the Constitution; a citizen obligation to participate regularly in meetings on local issues. To him, it was the essence of governing, keeping decisions close to the people by engaging them to interact with each other. It didn’t gain any traction and was quickly forgotten.

Jefferson and the framers weren’t interested in the price of eggs when it came to governing, they wanted to instill and perpetuate a sense of civic virtue, an innate sense of devotion, obligation and duty to the process of democratic-republican governing – at least for those few males who were eligible to vote and serve back then. According to Sagan, Jefferson

stressed, passionately and repeatedly, that it was essential for the people to understand the risks and benefits of government, to educate themselves, and to involve themselves in the political process. Without that, he said, the wolves will take over.

Jefferson died fifty years to the day the Declaration of Independence was made public on July 4, 1776 (John Adams, his bitter political rival who later, through correspondence between them, became his best friend, died hours before Jefferson on July 4, 1826). He lived those fifty years – as ambassador, vice president, president – with intimate knowledge that his nation was essentially weak, only near his death was he confident the nation would survive for posterity.

He understood that the United States was an experiment. There were no other examples of government “of, by, and for the People” at that time, only historically distant anomalies and an uncertain future. Jefferson would have agreed with Benjamin Franklin’s off-the-cuff answer after the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to a question of whether a republic had been created, “if you can keep it.”

Until 2016, I never doubted, warts and all, that the nation would endure. I believed, as President Barack Obama repeated often, in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s trust that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” January 6, 2021 bent that arc far out of shape. The aftermath of the past election will, I believe, make it irreparable for ages, certainly not in my lifetime, if ever.

It does indeed seem as though the wolves are taking over. The president of the United States considers citizens like me to be “vermin” and “scum.” We are called a range of things, from communists to Marxists to fascists, all of which sum up to un-American. An inability to be able to define nonsensical terms like “cultural Marxism,” “wokeness,” or claiming one group of people is “poisoning the blood” of a nation.

As we have seen in less than three weeks, the current executive branch does not believe in governing, it is focused on exercising power and implementing long-standing goals with the hope of making them permanent by keeping power for the foreseeable future. Its appointees will be expected to implement preset agendas in large part by denying a role for or legitimacy of the scientific method unless they can define it, make it malleable to fit pre-conceived conclusions, and intimidate anyone from claiming otherwise.

The goal is not to govern, but to dominate; not to believe, but to know; not to question but do. And anyone who gets in the way of a policy argument is an existential enemy, not a citizen or constituent. The evidence of just the past few weeks is undeniable (and can be found at any hour):

Congressman Ralph Norman (R-SC) publicly stated the former nominee to become the nation’s attorney general would “be the left-wing, socialists’ worst enemy.”

The current attorney general nominee is actively and publicly disrespectful to and elected senator the president considers to be “scum.” Confrontation and “whataboutism” will be expected of all appointees in future hearings and interactions, regardless of issue.

The incoming head of the Office and Management and Budget (OMB), the agency that puts pen-to-paper to propose funding levels for every part of annual federal discretionary spending has publicly said, “We want bureaucrats to be traumatically effected. When they wake up in the morning, we want them to not want to go to work because they are increasingly viewed as the villains,” he continued, “we want their funding to be shut down so that the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) can’t do all of the rules against our energy industry because they have no bandwidth, financially, to do so. We want to put them in trauma.”

“To my friends, who are upset, I would say with respect, call somebody who cares, they better get used to this…” John Kennedy (R-LA) on elimination of departments and agencies without congressional approval.

Since January 20, it does seem as if a 21st century version of Pandora’s Box hasn’t been any easier. Of all the evils unleashed, finishing off the legitimacy and appreciation of the scientific method – at least in the United States, although its effect will reverberate indefinitely around the world – may well be the most ultimately damning malevolence.

As of now nothing can be verified, nothing can be acknowledged; everything is up for grabs and subject to changing definitions that don’t jibe with what we see with our eyes to reasonably and figure out with minimal logic. After all, you don’t have to put your hand in fire to know you will get burned.

The most pernicious example of this new reality was on display in the recent tragic collision between a jet and helicopter near Washington National Airport. Without any evidence, President Trump’s first public remarks on the accident baselessly speculated that Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies were likely at the root of the accident. Removing all doubt about any subtext, his press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, followed up:

When you are flying on an airplane with your loved ones, which everyone in this room has do you pray that your plane lands safely and gets you to your destination or do you pray that the pilot has a certain skin color? I think we all know the answer to that question. And as President Trump said yesterday, it’s common sense.

Let’s be clear about what each actually said. They took the Linnean chart above and translated it into code their followers understand. By unmistakable implication, both say only white males are capable of flying aircraft and that passengers need to know the gender and racial identity of the pilots. Immediate elimination of so-called DEI-related programs and policies, as is ongoing now, is based purely on this overriding conviction and delusion, not on scientific fact or observable reality.

This will be the first of a number of occasional articles in which I tackle the “whys” in coming months. If you only remember one thing, remember this: Nothing matters without a verifiable scientific method.

Carl Sagan summed it up perfectly in the last words he would ever write:

Education on the value of free speech and the other freedoms reserved by the Bill of Rights, about what happens when you don’t have them, and about how to exercise and protect them, should be an essential prerequisite for being an American citizen — or indeed a citizen of any nation, the more so to the degree that such rights remain unprotected. If we can’t think for ourselves, if we’re unwilling to question authority, then we’re just putty in the hands of those in power. But if the citizens are educated and form their own opinions, then those in power work for us. In every country, we should be teaching our children the scientific method and the reasons for a Bill of Rights. With it comes a certain decency, humility and community spirit. In the demon-haunted world that we inhabit by virtue of being human, this may be all that stands between us and the enveloping darkness. (emphasis added)

Photo: Detail, Crisóstomo Alejandrino José Martínez y Sorli, Plate for the ‘Atlas Anatomico (unpublished, printed 1740), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

[1] Reverse side of historic plaque:

[2] As I wrote in an earlier article, “I prefer the term conspiracism, coined by Thomas Milan Kunda, a retired professor from Plattsburgh, New York, rather than ‘conspiracy theory’ because it is more accurate. The word ‘theory’ alone implies a certain logic and legitimacy, which, in this case is not earned or valid. A conspiracism, on the other hand, is ‘a mental framework, a belief system, a worldview that leads people to look for conspiracies, to anticipate them, to link them together into grander overarching conspiracy.’” From Conspiracies of Conspiracies: How Delusions Have Overrun America (University of Chicago, 2019).

[3] This discussion of Linnaeus is based on Jason Roberts’ Every Living Thing: The Great and Deadly Race to Know All Life (Random House, 2024). It is something of a dual biography of Linnaeus and George-Louis Leclerc de Buffon and their legacies on science today. Although they were pioneering contemporaries in a new field, attempting to classify all things natural from geology to humanity and everything in between, they never met.

[4] Quotes and comments for this section can be found in The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Sagan died in 1996 as he was being treated for myelodysplasia (MDS) at The Hutch in Seattle. MDS is a cancer that shares many characteristics with myeloma, but instead of plasma cells becoming malignant, red blood cells don’t mature. Untreated, MDS will likely develop into acute myeloid leukemia (AML).