Nothing about myeloma or cancer history today. Just wanted to share something I started more than a year ago before setting it aside. Now it’s an exercise to try to exorcise my writer’s block. This is part one, part two in a couple of days. I’ll be getting back to the subject of this Substack next week.

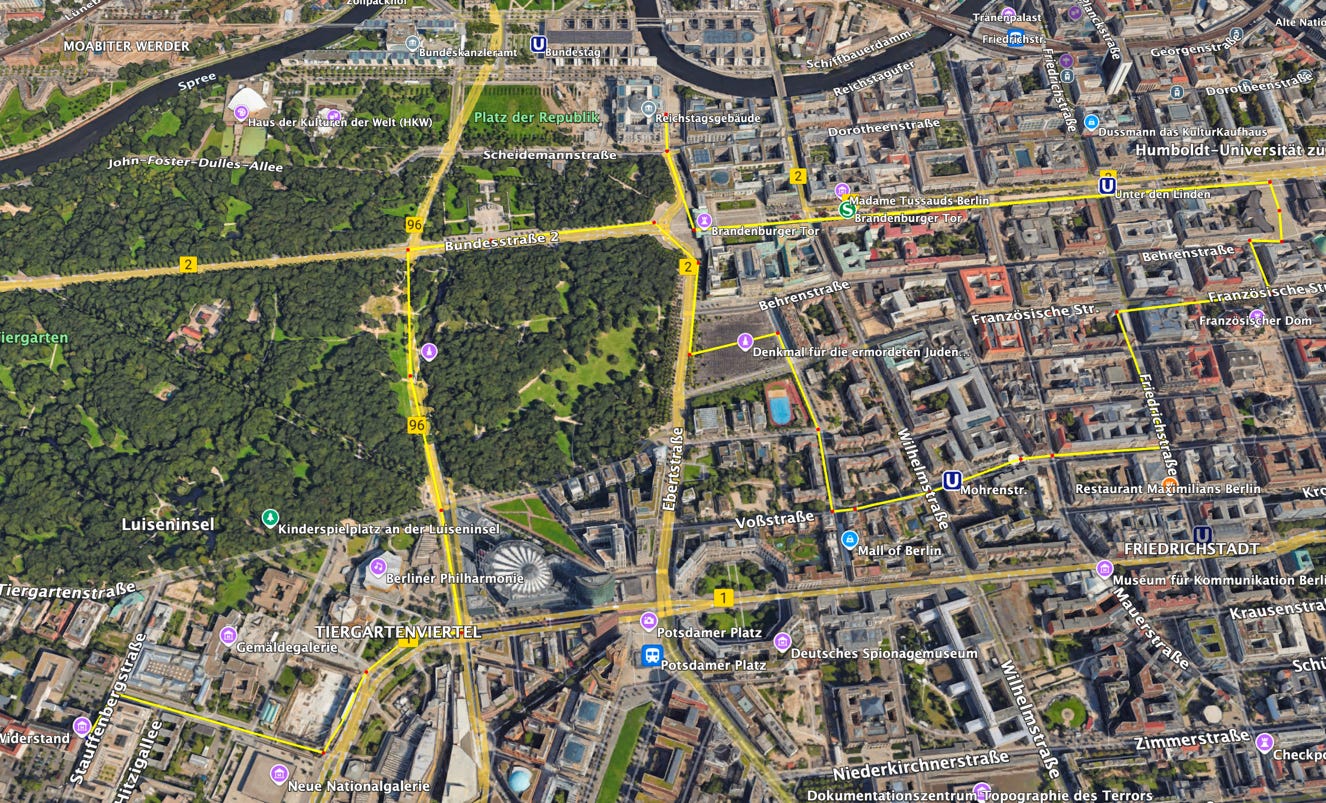

October 3 was the Tag der Deutschen Einheit (German Unity Day), a national holiday commemorating Germany’s reunification, celebrated since 1991[1]. It reminded me of a walk I’ve taken in Berlin many times in past years, and still occasionally do in my mind. Three-and-a-half miles, taking up the better part of the day.

Please join me if you’re interested. We can meet on the eastern side of the Reichstag building, the corner is closest to the Spree (sh-pray) River. This part of the river once connected the Berlin Wall. Where we’re standing was once West Berlin, across the river was East Berlin. The Wall continued on just parallel to this side of the Reichstag, and went south along the street, past the iconic Brandenburg Gate.

Until May 8, 1945, the end of World War II in Europe, the Reichstag was Germany’s capitol building. It has been so again since Germany’s reunification. In between those dates, it was a ruin, then a museum. Between 1933-1945, it housed a listless rubber stamp for Nazi policies.

Take a close look at the building. You can still see the thousands of stone patches covering up the holes caused by bullets and mortar of the invading Soviet army that took the city to end World War II. After the war, the city – and the nation itself – was partitioned among the four victorious Allied nations: the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. In 1949, the nation was split in two, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), consisting of the Soviet Zone, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), which was made up of the three remaining zones. The same was done with the city of Berlin; it became a land-locked island in the middle of East Germany.

Until August 11, 1961, it was relatively easy to travel between East and West Berlin. But too many from the East stayed in the West, draining its population, leading to the construction of the Wall. After that it was practically impossible for those in the East to go to the West. A few did, many died as they tried to flee the East. Some were shot in the Spree right within sight of where we are standing. The Brandenburg Gate, which we’ll pass by a couple of times today, was just a few hundred yards south of the Reichstag, on the “other” side of the Wall.

I had been to East Germany a number of times since 1975, to visit family after a loosening of travel restrictions for West Germans who wanted to travel to the East. But not the other way around. The first and only time I was in West Berlin was in August 1989, when Mikhail Gorbachev’s Glasnost and Perestroika reforms were becoming visible. At the time, I thought it might actually be only five years or so before the Wall came down. The idea that it would happen in a little more than two months could have been considered to be certifiably nuts in August 1989.

Between the Reichstag and Brandenburg Gate stood one of the many infamous guard towers on the eastern side of the Wall, with soldiers monitoring the death strip of booby traps with dogs, automatic machine guns, and manned watchtowers overlooking the Wall, looking for “threats” on the western side. I can remember looking up and seeing a pair of binoculars watching me as I walked along the eastern edge of the Tiergarten, Berlin’s large public park, its version of Central Park.

Now that tower, death strip and Wall are gone. No traces can be seen except for occasional brass strips in the ground commemorating where the Wall once stood, but you have to look for them. Now there are regal government buildings which bookend the Brandenburg Gate, the French embassy on one side, the American on the other. We’ll continue down and take a left through the Gate, something that was impossible to do between 1961-1989.

As we pass through the Brandenburg Gate – where Nazi celebratory marches usually began – we’ll continue to straight, down Unter den Linden, the broad avenue that Berliners often compare to Paris’s Champs Elysee. But it’s quite different, much more understated, with rows of Linden trees lining each side of the pedestrian median, but they don’t inspire grandeur. (Robert Kyle once described to me how disappointed he was in seeing it the first time after reading about it for years. It didn’t measure up to the hype he was expecting.)

We’ll walk past the posh Hotel Adlon and looking right to see the ultra-modern British embassy. As we cross Wilhelmstrasse, which, for more than a century, was Germany’s version of Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, we’ll see an identical row of nondescript buildings extending down on the right side of the street. Before they were built, there stood a row of imposing government ministry buildings. It was on this street where the infamous films were taken of Hitler saluting marching, torch-bearing soldiers and Nazi party members from a balcony after he became chancellor to celebrate his sixth year in power in 1939. We’ll cross this street again later in our tour, at the end of the row of the existing buildings, but, for now, we’ll continue down Unter den Linden.

We’ll pass the imposing, block-long Russian embassy. The Stalinist architecture displays power, when it was the Soviet embassy during the years of East Germany’s existence, a reminder to everyone that they were really in charge.

Few, even those who claim to know a lot about the history of the Third Reich, appreciate the intense rapidity of how the country changed after January 30, 1933. German conservatives, led by former chancellor Max von Papen and wealthy industrialists, were sure that by installing Hitler as chancellor they would control him, he would be their puppet, so to speak. Plus, the gravity of the responsibilities would surely temper his past extremist views, or so they were absolutely (mistakenly) sure.

Although conservatives hated almost everything about the Weimar Republic represented in its short fourteen years of existence, they were under the assumption that the structure of governing, however imperfect, would continue. Even though Hitler’s Nazi party had the most votes in the most recent election, it never once received a majority. In the last national election in November 1932 – the last free elections until 1945 – the Nazi party received slightly more than 33% of the vote, down from its high-water mark of 37% in the July 1932 elections.

But Hitler had other ideas, ones he clearly outlined in his convoluted, racist, and hateful book Mein Kampf (My Struggle). Within a month, the process of Gleichschaltung, politely defined as the alignment of party dogma with national government, in reality, the lightning-quick removal of obstacles to do so, was virtually complete. Monied conservatives who were sure of their master stroke to corral Hitler into irrelevancy as he fulfilled their wishes, were pushed aside and made irrelevant.

The key event to solidify Nazi control over government occurred on February 27, 1933: the Reichstag Fire. I won’t get into the history and conspiracisms[2] of the Fire itself, but here’s why it’s important for our tour: it provided the opportunity to declare a national state of emergency, dramatically accelerating the Nazi plan of Gleichschaltung, a deliberate plan to coopt and control the nation’s legal, social, political, and cultural institutions with Nazi party principles and consolidate Hitler’s power into a dictatorship. Other political parties were banned, martial law was declared, and the free press was quashed – while the fire was still burning, well before any facts were known.

On that very night, journalists who had been critical of Nazis in previous years were arrested. At the top of the list was Carl von Ossietzky (oss-EE-ets-kee), the editor of the left wing political and cultural magazine, Die Weltbühne (The World Stage), which was the earliest, most consistent, and unrelenting critic of the Nazi Party from the time it was a fringe group of rabble rousers through its assumption of national power. Its most prolific writer, Kurt Tucholsky, went into exile to Sweden a year earlier. He begged Ossietzky to leave as well. Die Weltbühne was targeted for elimination for years by the Nazis – its – and the Reichstag Fire gave them the excuse they needed to make his arrest and the publication illegal.

Ossietzky had recently been released from prison after being convicted a few years earlier of publishing evidence that Germany was rearming in defiance of the terms of the Versailles Treaty which ended World War I. Although it was commonly known that Germany was doing so – well before Nazis took power – the right-wing court held a farcical trial to convict him. He was soon to become one of the first sent to one of the newly created concentration camps.[3]

After being kept in the camps and incommunicado for years, an international campaign, which included German exiles Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, and Willy Brandt[4] to award the Nobel Peace Prize to Ossietzky in 1935. But it was not awarded that year.

Until then, the Peace Prize had been a sort of lifetime achievement award. The campaign was successful in having the Prize awarded to Ossietzky in 1936. That established a precedent, which is now common, to make the Peace Prize a way to publicize and shine a light on a current or emerging human rights issues. Hitler did not allow Ossietzky to receive the award, in large part not to diminish the illusion he wanted to present to the world through the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Ossietzky died in 1938 as a result of the abuse he received in concentration camp detention.

Now, after walking a few more blocks, we’ve reached the Bebelplatz, formerly known as Opernplatz, a large open square to our right. Until now, much like an opera, everything has been an overture of sorts. Now our tour truly begins.

It was here, on May 10, 1933, that the final scene of the first act of Gleichschaltung played out, a book burning led by Josef Goebbels, the Third Reich’s propaganda minister. Seen initially as a minor, insignificant event, right-wing students at German universities throughout the nation planned public demonstrations to underscore their commitment to Nazi authority. The book burnings would “cleanse” the universities of “degenerate” influences lurking within their libraries. As the new reality of Gleichschaltung was settling in with Germans, Goebbels soon recognized the students’ plan as a way to consolidate and express the new power. He pushed aside the student leaders to personally lead the largest and most prominent book burning at the Opernplatz.[5]

The location was perfectly suited to consolidate and convey Gleichschaltung, not just because it was a large, stone covered square along one of the most prominent streets in Germany, but because of what surrounded it. As Goebbels yelled out the names of the authors whose books he threw in the growing pyre, he did so with full awareness of its symbolism.

Bordering the square on the east was the pink colored German Opera; to the southeast, St. Hedwig’s Cathedral, a Catholic church built during the reign of Prussia’s Frederick II, long considered a golden age of German supremacy; to the west was the Humboldt University’s law library; and to the north, across Unter den Linden, was the entrance to Humboldt University, the first modern university which introduced methodical study of subjects and baccalaureate degrees, which are now practically universal. In essence, the Opernplatz book burning was sanctified by German culture, religion, law, and academia, legitimizing everything Nazis wanted to convey complete power to the world.

Today a monument commemorates the Opernplatz book burning, but you have to know where to look for it; it doesn’t stand out. In the middle of the square, now a mosaic of granite and cobblestones, is a plexiglass window that many people walking across do not notice. During the day, it seems unremarkable, an odd anomaly, and it’s somewhat difficult to see what’s underneath.

At night, however, it’s lit up from below, glowing upward, much like a burning pyre, but with a much different intent from that of May 10, 1933. Looking down, an entirely white room can be seen, bordered by empty books shelves. It summons, literally begs people to look down and contemplate what a world without books might be like. A world Nazis and all dictatorships wish for, one in which people wouldn’t be able to think “unapproved” thoughts.

Today’s law students at the Humboldt University can look out of the windows of its library to see exactly where those books were burned, hopefully reminding them, constantly, of the purpose of their studies. And everyone can take time to contemplate what was lost and eventually recovered. Hopefully to never be lost again.

Now let’s walk past the far corner of the law library, taking a right, a left on the next street, before taking a right at the next. To our left is a large block, the Gendarmenmarkt, bordered on both sides by the identical French and German Cathedrals which frame a large square. The buildings and square were heavily bombed and rebuilt, but not completely until after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In between the cathedrals, the square is in front of the Konzerthaus Berlin, which was the premiere concert venue in the city. After 1933, Ludwig van Beethoven and Wolfgang Mozart works would continue to be performed, but never those of Gustav Mahler or Felix Mendelssohn, who, despite having converted to Christianity during their lifetimes, were only considered to be Jews by the Nazis (not that it should ever matter in a sane world). It was rebuilt by East Germany in the 1970s and is still a popular concert venue. Today, directly behind it, is the Hanns Eisler School of Music (Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin), named for the avant-garde composer of the Weimar era who was exiled in the United States after 1933, collaborated many times with Bertolt Brecht and later composed East Germany’s national anthem. (The West German, and unified German, national anthem, was adapted from a Joseph Haydn composition.)

We’ll keep walking straight one more block until we reach Friederichstrasse, a main street of Berlin’s retail commerce. A few blocks to the right is a train station once called the Tränenpalast, or the Temple of Tears. It was entry and exit point for West Germans and tourists to visit East Berlin, called so because it was a place for tearful reunions and goodbyes. Instead of going there, however, we’ll turn left and walk a couple of blocks.

Along the way on the sidewalk we’ll look down carefully to locate another hard-to-find monument, just one small bit of the world’s largest memorial, one that is spread throughout German cities and has grown to include twenty-three more European nations: Stolpersteine. A Stolperstein is a small, cobblestone-sized brass square imbedded permanently – as permanent as human history will allow, that is – in the ground. Roughly translated as “stumbling stone,” a term used for a cobblestone that sticks out a little, causing some to trip and stumble, or to “stolper.” Each one is a testament to individual victims of the Holocaust and commemoration of where each one lived or worked.

Once noticed, Stolpersteine are hard to miss when walking through cities and towns, even in the quietest residential neighborhoods. The idea was conceived as an unapproved “guerilla art project” – at first being placed in secret – by artist Gunter Demnig in 1992. His intention was to name the victims of Nazi terror by embedding brass cobblestones on the sidewalks and streets of where they lived, including information of about their birthdate, their fate after being arrested and the date of death (Germans are consummate record-keepers). Some commemorate those who survived.

Demnig received both praise and condemnation for his idea. Praise from cities, which have now made the placing of stones events throughout Europe. Some now number in the hundreds and thousands in more than 280 cities throughout Europe. The 100,000th was set in Nürnberg, Germany on May 26, 2023. They continue to be placed as more victims’ stories are identified.

The one we’re looking for is in front of a large department store. It reads “Here lived, Davisco Asriel, born 1882, deported January 25, 1942, murdered in Riga.” Asriel once owned a thriving department store at this site. He was Jewish. Being an owner of a prosperous business on one of Berlin’s most fashionable streets did not exempt him from being arrested and transported in a crowded freight car, most likely standing because there was no space to lie down, relieving himself where he stood because there were no toilets, for more than twenty-four hours, perhaps longer. The date of his death, January 25, 1942 indicates he was killed before the existence of extermination camps in eastern Europe. The decision to establish them was made on January 20, 1942 at the Berlin Wannsee Conference.

Asriel was likely transported to a forest south of Riga, Latvia called Rumbala. The victims were forced to get out of the trains, march to prepared pits, ten meters by ten meters wide and at least three meters deep, forced to strip so that their clothing and belongings could be cleaned and sent back to Germany, told to get into the pits, lie down on top of previously executed persons. Each person was shot in the head. The procedure was repeated until more than 138,000 Jews from Germany and neighboring nations were killed.

Stolpersteine belie the myth that most Germans and people in other nations where Jews and political opponents were rounded up were unaware of the Holocaust. While witnesses in these areas may not have been aware of the specifics to extermination of their former neighbors, they could not ignore the terror of arrests, marching groups of people to train stations, immediate experiences of people being forced out of their homes through police action and marching them to train stations. Witnesses might not have been aware of eventual fates of those rounded up, but they could not claim to have seen nothing.

Some critics claim Stolpersteine, placed where people can step on them, was disrespectful to the memory of the victims. But Demnig’s artistic collaborator, who makes every single stone had a more compelling explanation. To observe a Stolperstein, one has to stop and bow one’s head to read; it becomes a moment of silent contemplation and respect for each individual. The act is one of remembrance, and most all, reverence for each individual’s life and fate. Demnig’s inspiration was a verse from the Torah: People are forgotten only when we forget their names.

[As I was finishing this article, it was reported that all ten Stolpersteine placed in Zeitz, Germany were ripped out of the ground and stolen on October 8, 2024. Zeitz is in the extreme south of the state of Sachsen-Anhalt, in the former East Germany, where the neo-Nazi party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has been in ascendancy in recent elections. In the last communal elections, 33% of Zeitz voters cast their ballots for AfD candidates.]

As we continue to walk south on Friedrichstrasse, we’ll take a right at Mohrenstrasse. For the first block we’ll get a good view of the Stalinist architecture that once dominated the design of public buildings behind the Iron Curtain. On the next block we’ll see the entrance of the Mohrenstrasse subway stop, walk down the steps, along the length of the platform, and up the stairs to the street on the other side. Why? To see the red marble walls lining the walls the ceiling.

The marble rectangles are historic evidence of repurposing. They once lined the inner halls and office walls of Hitler’s chancellery, where he lived and had his offices, the Nazi version of 10 Downing Street or the White House. When we emerge from the subway stop, we’ll walk straight for a short block and cross Wilhelmstrasse, where Mohrenstrasse changes names to become Vossstrasse (Voßstraße in German).

In front of us is the southern end of the non-descript, somewhat ugly, row of buildings we first saw when we looked down Wilhelmstrasse to see the British embassy. These buildings served as exclusive housing for the East Germany’s ruling elite when the Berlin Wall stood. On the corner, where a Chinese restaurant now occupies the bottom floor, is the former site of Hitler’s chancellery.

In stark, somewhat ironic contrast to its evil past, this corner now houses, on its bottom corner, a pharmacy and Chinese restaurant. Directly on the other side, where we will next walk past, is the neighborhood kindergarten. Pondering how outraged Hitler would have been to learn of what became of his power center might be the only instance his memory could induce an ironic chuckle.

Before we cross the street, look to the right for a seemingly random crooked pole above the trees. In daylight it’s harder to see without knowing where it is. It stands out at night when lit up, revealing, upon closer inspection, a silhouette, the face of Georg Elser. His story is told in the film Elser – Er hätte die Welt verändert(literally translated as Elser – He Would Have Changed the World, the version marketed in the United States is titled Thirteen Minutes).

Elser was a relatively nondescript, apolitical skilled machinist and handy man from southern Germany who was appalled at the rise of Hitler. Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 transformed his revulsion into a commitment to try to kill Hitler to stop his regime from leading Germany to what Elser believed was a catastrophic disaster for the world. He saw his opportunity in an annual commemoration of Hitler’s failed attempt to violently overthrow the Bavarian government in 1923, known as the Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler was given a token sentence at Landsberg prison, where he lived in comfort while dictating the book Mein Kampf,[6]presaging the catastrophic malevolence to come.

Like all Germans, Elser knew the annual event was always held at the site where the Putsch ended in violence and death, Munich’s Bürgerbräukeller. Three days prior to the annual Nazi ceremony, Elser went there, blended in, and hid there when it closed. Each night, he followed the same routine, hollowing out a section of the column behind where the podium would be to place and hide his homemade time bomb. The spot was located behind a hanging Nazi banner, hiding his handywork. He set the detonation time to coincide with Hilter’s culminating remarks, which were always given at 9:30 pm, the exact time his followers stormed into the hall.

Virtually every prominent Nazi was in attendance. The ceremonies began with the presentation of the “bloody flag,” the actual flag used by Nazis in 1923, still splattered with the blood of one of their “martyrs,” Horst Wessel, after whom the unofficial Nazi anthem was named. Weather conditions would not allow Hitler to fly back to Berlin as scheduled; instead he would take a night train scheduled to depart promptly at 9:31 pm, moving the time of speech up to 8 pm. The speech, fed by the emotion of the evening, was vintage Hitler, at 9:07 pm Hitler left for his train. At 9:20 pm, a bomb that was concealed in the column directly behind the Bürgerbraükeller speaker’s podium behind a Nazi banner, exploded. Thirteen minutes. It added one more chapter to the myth of Hitler’s invulnerability.

Elser left the afternoon of the bombing and tried to escape by train to Switzerland, where he was detained—just 35 minutes before the bomb detonated—because of his suspicious behavior. He was interrogated by head of the criminal police, Arthur Nebe (ne-beh), who was never able to convince his superiors that Elser acted alone – how could a common laborer, they reasoned, be able to do such a thing without being part of a larger conspiracy? As a result, Elser received special treatment, living in relative comfort, by concentration camp standards, in the Sachsenhausen camp just north of Berlin, as they tried to coax information about his so-called conspirators, with Hitler keeping him alive. Near the end of the war, however, he was transferred to Dachau to be executed shortly before the camp was liberated by the Allies.

We’ll continue down the street, take the next right, and about a block and a half down, to our left will be a nondescript parking lot behind and parallel to the row of buildings on Wilhelmstrasse. Underneath the parking lot is former site of Hitler’s bunker, which is now filled with dirt and inaccessible. Somewhere on that parking lot was where, shortly after Hitler and his new bride, Eva Braun died by suicide, some staff tried, unsuccessfully, to burn their corpses. They were found by the invading Soviets and promptly disappeared.

Looking to the northwest, across the street corner, we can see the massive monument to the victims of the Holocaust, filling the street block with a collection of variously sized black stones set in a grid. The placement of the memorial within sight of where the bunker was is a fitting, almost ironic, juxtaposition. Walking among the blocks of uneven height laid out on geometric stone paths that undulate randomly to cause imbalance, claustrophobia, and confusion to somewhat get a sense, through art, of the hopelessness felt by victims of the Holocaust. After emerging on the other side, we’ll walk up the street, right along the path of where the Berlin Wall stood, until reaching the Brandenburg Gate to take a left into the Tiergarten.

After a hundred yards or so, to our right, is one of the Soviet World War II Memorials, which during the time of the Wall, was kept off limits by a twenty-four hour Soviet honor guard. Now we can walk all around it to see another use of the white marble that was once was the outside of Hitler’s chancellery. The Soviets used the rest of it to build a second monument to honor its war dead, thousands of whose bodies are buried under a large hill, in Treptow Park in the far eastern part of Berlin.

Now we’ll continue walking up the street and take the first left to make our way through the Tiergarten. As we walk, imagine the park, the peaceful, quiet areas that defy the notion that we are in the middle in one of the largest, bustling cities in Europe. It’s impossible to visualize that this park was stripped clear of its animals and foliage at the end of World War II, as desperate locals, homeless and starving, tried to survive in the days and months after the city was destroyed.

After a few hundred meters, we’ll emerge to see a modern new office buildings, which are at the back of a complex of high rise buildings that make up the bustling commercial Potsdamer Platz. All the buildings were constructed after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The location of the building to our immediate left was where the Volksgerichtshof, the People’s Court of Justice, was located before it was bombed in 1945. It was one of the most infamous examples of legal and administrative evil of the Third Reich.

The Volksgerichtshof was created to weaponize the “Stab in the Back” conspiracism (der Dolchstoss): that Germany lost World War I because left-wing politicians and Jews undermined the army on the Western Front, that they were not defeated on the battlefield. “A fundamental reason for the failure of the First World War to bring peace and stability to Europe and the wider world lay in the Germans’ refusal to accept the fact they had lost.”[7]

This fiction, this willful lie, was the basis for establishing a legal structure, parallel and superseding to existing civil and criminal court system. It provided statutory legitimacy to virtually every one of the most heinous, evil actions and consequences of the Third Reich, from the surveillance and persecution of the German people by the state secret police, the Gestapo, to Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass” of November 9-10, 1938, when German Jews were legally terrorized and many of their synagogues burned, to the Holocaust itself.

The architect for turning this conspiracism into the Volksgerichtshof was a rabid Nazi, Roland Freisler,[8] who went on to became its first – and only – chief judge. He held court on the very site that once stood to our left; similar courts were established throughout the nation. “Freisler wanted a justice that handed down fast and hard verdicts. Most of all against ‘political criminals’ who, for Freisler, were the worst traitors and enemies of the state.”[9]

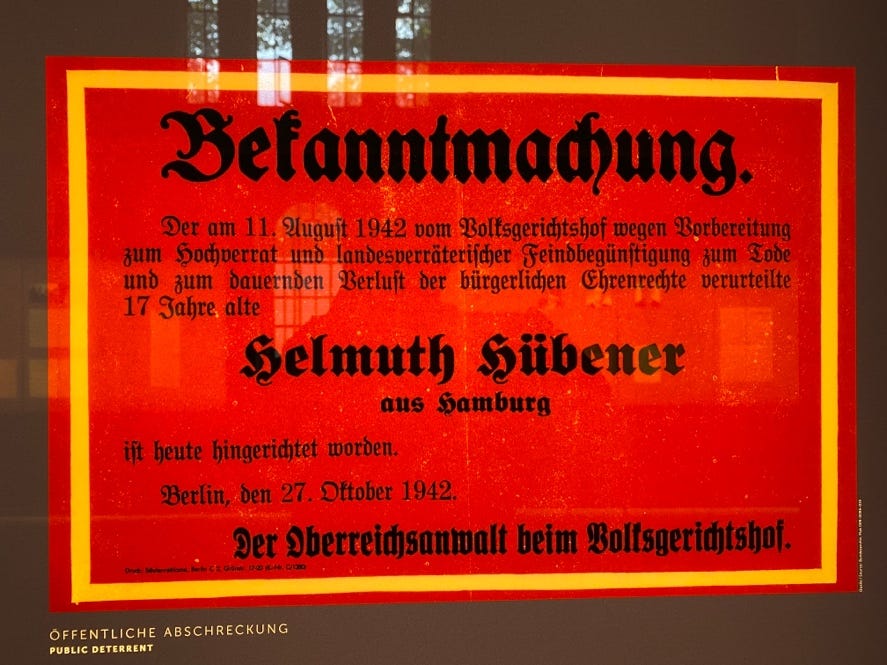

The purpose of the court was not to dispense justice, but instead to annihilate opponents of Naziism with political “laws” Freisler concocted to establish the Volksgerichtshof.[10] Moreover, the court’s proceedings were intentionally public in order to intimidate anyone from doing anything that might land them before Freisler and his network of judges. Announcement of death sentences printed on bright red posters were placed on walls and poles in the communities and neighborhoods after the condemned victims were put to death.

Verdicts with printed and filed with stereotypical German attention to detail, “In the name of the German people.” Over the course of the Volksgerichtshof’s existence from 1934 to 1945, 16,342 persons were accused, 5,243 were executed, 7,768 received prison sentences, including being sent to concentration camps where many, if not most, died. Although 1,089 persons were acquitted, most were ostracized by their communities, families, and unable to find employment. Just being accused deterred people from associating with those who were cleared for fear of being persecuted themselves.

Freisler would often take charge of high profile trials outside of Berlin, as he did on February 22, 1943 with the farcical “trial” of the White Rose resistance group. Most notably associated with Hans and Sophie Scholl, siblings who were students at the Ludwig-Maximilian’s University in Munich, the White Rose tried to inform people about the lies they were being told about military success in the Soviet Union. Just four days earlier, the Scholls and fellow students and teachers were arrested after they were seen placing flyers in the halls of the university. Freisler immediately flew down to preside over the trial of the Scholls and their fellow student, Christoph Probst, to berate and convict them. All three were beheaded that evening. There were no appeals or delays of sentences of Volksgericht verdicts.

Freisler escaped post-war accountability when, on February 3, 1945, he was crushed by falling rubble caused by a British bombing of the court building. But the injustice lived on. His widow received a generous pension from the German government until her death in 1997 based on the perverse reasoning that Freisler never had to personally account for his crimes in post-war Germany – because he was dead! – and never faced legal sanction for implementing travesties of Nazi laws while he lived. And virtually all the surviving judges of the Volksgerichtshof went on to serve long legal and judicial careers in the post-war government of the Federal Republic of Germany.

We’ll see some examples of the court’s actions in the next two stops on our tour. We’ll walk to the end of the block, take a right, and walk past the gaudy, 1960s architecture that now houses the Berlin Philharmonic, long considered one of the top two orchestras, along with Vienna’s, in the world. It’s worth a visit if you have time to see a concert there, but for now, we’ll continue on one more block, take a right, and walk another couple of blocks until we reach Stauffenbergstrasse, the building is across the street to the left.

The Bendlerblock is a group of connected buildings surrounding a large courtyard; it can be compared to the American Pentagon – in function, not size. During the Third Reich, it was the administrative center of the German War Ministry. In 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg was assigned there as a military war planner after losing his left eye, right hand, and two fingers on his left hand in the North African campaign in 1943. While recuperating from his wounds in Berlin, he became increasingly disillusioned with the course of the war and joined a group of former and active military members who were plotting to overthrow Hitler.

Stauffenberg was at the center of the most well-known attempt to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944. He was sent to the command center of the eastern front, known as the Wolfsschanze (the Wolf’s Lair), located in East Prussia, which is now part of northeastern Poland, to brief Hitler and the high command. Carrying a time bomb in his briefcase, Stauffenberg set and placed it under the table where Hitler was updated, before using an excuse to leave and fly back to Berlin.

The bomb detonated, but the weight of the oak table shielded Hitler, leaving him with minor injuries. Others were wounded and killed and, much like Elser’s failed attempt in 1939, Hitler’s aura of invincibility among his supporters grew. Stauffenberg mistakenly thought he had succeeded when he returned to Berlin, when his fellow conspirators planned to take command of the army and government. But as the day progressed, it was clear that not all had gone according to plan.

The leader of the military part of the resistance was Ludwig Beck, the former German Army chief of staff, who resigned his post in 1938 because he opposed plans to prepare for a European war. He and others were on the verge of an assassination attempt on Hitler that was called off after British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain negotiated a treaty with Hitler in 1938, mistakenly believing it would avert war and bring “peace in our time.”

Beck was in the Bendlerblock on the evening of the July 20 when it became clear the plan did not succeed; those loyal to Hitler quickly began to arrest the leaders. By 10 p.m., realizing they had failed, Beck shot himself. Although he did not die immediately, one of the arresting officers immediately finished him off with additional shots. Stauffenberg was arrested in his office soon after and summarily executed by a firing squad shortly after midnight, along with his closest colleagues, Werner von Haeften, Friedrich Olbricht, and Albrecht Ritter Merz von Quirnheim, in the Bendlerblock courtyard.

In order to quell any uncertainty among the German population about who was still in power, Hitler delivered a short radio address to the nation at 1 a.m., to let the nation know he was alive, in charge, and exhorted the military to not obey any commands of any remnants of the soldiers who tried to remove him. He said it was another “Stab in the Back” attempt after beginning his broadcast with the claim that the assassination attempt was carried out by “a very small gang of ambitious, unconscionable and altogether stupid, criminally dumb officers.”[12] As the next days and weeks proved, however, they were anything but. It was later estimated that there were as many as 7,000 arrests and 4,000 executions related to the July 20 action. Of those implicated in the conspiracy, 50% were military officers, eighteen were generals. Additionally, twelve served in the foreign ministry, and a large number were members of the conservative German nobility class.

Many of the civilians involved belonged to the Kreisauer Kreis (the Kreisau Circle) a diverse circle of intellectuals, government officials and bureaucrats, and former elected officials of the Weimar Republic, the government the Nazis replaced. They occasionally gathered on an estate in Kreisau, Silesia (now Poland) owned by Count Helmuth James von Moltke, an attorney in the Defense Ministry with a strong military family history.[13]

The secretive retreat-like meetings involved long-ranging discussions about how Germany would be governed in a post-Nazi era covered the full range of domestic and foreign policy issues. Moltke envisioned a European alliance of nations based on individual civil rights and a Christian ethic of shared, interrelated interests and obligations to avert future wars, foreshadowing today’s European Union. Additional, smaller, more focused gatherings were held in Berlin, often at the apartment of the Kreis’s co-leader, Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, an former attorney in the agricultural ministry whose career was stymied because he did not join the Nazi Party. Wartenburg began to hold secret meetings to draft a new German constitution shortly after Kristallnacht in 1938.

German Protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer participated in some of these gatherings. Bonhoeffer opposed the Gleichschaltung of the Protestant Church with the Nazi government – in essence, making it directly dependent on Nazi policy – and created the Confessing Church,[14] which was not under Nazi administration, thus making himself suspicious to the state. He initially felt assassinating Hitler was immoral and forbidden, but by the early 1940s changed his thinking, realizing it was likely the only way to restore a religious ethic to Germany. This was a key moment in linking the Kreisauer Kreis with the military resistance movement led by Beck.

Wartenburg was Stauffenberg’s cousin. When the later was reassigned to Berlin, he was invited to the meetings in Wartenburg’s apartment and became an important figure in linking the two groups. After the demise of the July 20 plot, participants of both of the loose alliances were implicated.

Show trials led by Freisler began within days after July 20. Among the first of thousands tried and executed were Wartenburg on August 8. Bonhoeffer was arrested, sent to a few concentration camps and executed shortly before the end of World War II. Moltke was already under arrest on July 20, but his leadership of the Kreisauer Kreis was soon exposed and he was executed in early 1945.

His widow, Freya von Moltke, also an attorney (who graduated from Berlin’s Humboldt University law school, which bordered the site of the May 10, 1933 book burning), wrote about and publicized the martyrdom of her husband and his associates after the war. She went to South Africa to fight against apartheid in 1950 before returning to Germany in 1956 to resume writing about German resistance and its implications for the young West German government. In 1960, she moved to the United States, later becoming a citizen, and died in 2010 at the age of 98 in Norwich, Vermont, where she is buried. A foundation in her name keeps the principles of European freedom and the Kreisauer Kreis alive today.

July 20 has become a sacred German day of commemoration, but its legacy is not always without certain shadows that continue to linger. By the early 1950s, at least 59% of the German population still considered those involved in the plot to kill Hitler to be traitors. This didn’t begin to change until a state’s attorney, Fritz Bauer, in 1930 the youngest judge in Weimar Germany who lived in exile from 1933-1949, charged a former rabid Nazi who stood as a candidate from a new-Nazi party in the early 1950s with lying about the July 20 plot. The trial became a national reckoning and educated many Germans about the reality of lies they had been told for years with details of the repression in their midst.

One of the plotters later executed was Arthur Nebe, the same person who interrogated Georg Elser in 1939. Nebe went on to become a notorious leader of one an Einsatzgruppe, special divisions of death squads that killed countless Jews, Poles, and other eastern Europeans as the German army moved eastward toward the Soviet Union. He only became involved on the fringes of military plotters of July 20 when he became convinced that the war was lost. Like many involved, his interest was in saving the existence of the German nation and not necessarily to be held responsible for its atrocities. One can only speculate, had the plot succeeded, how people like him might have been dealt with.

And that points out another uncomfortable truth about the nature of political engagement, accountability, and actions. The truth is that many of the resistors to Naziism were late to the game. Before Hitler came to power, many of them were either openly supportive of or secretly sympathetic to the Nazi Party. It promised order, stability, and standards of morality (or so they thought) that post-World War I Weimar Germany, in their views, did not. They remained silent or supportive and their perceived opponents – social democrats (liberal and moderate), communists, and “outsiders” like Jews or immigrants from other nations – were the causes of social and political instability. Even after many began to perceive and understand the injustices, crimes, and atrocities perpetrated in their names by the Nazi government, the old enemies remained suspect.[15]

Even Martin Niemöller, whose public statements were manufactured into a quote that greets visitors to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, admitted to having this inconsistency in 1933. As with all members of the Confessing Church, his primary concern for Jews was limited to those who had converted to Protestantism. He admitted that “communists were no friends of the Church, actually the opposite, they were its declared enemies, and that’s why we remained silent. And then came the trade unions, and the trade unions were also no friends of the Church, and we had little contact or even none at all and said, well, better to let them fight their own battles.”[16] Retrospective fictions are more appealing that actual realities.

Today the Bendlerblock houses the German Resistance Memorial Center (Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand). It’s not a museum that contains historical objects, or more precisely, the site itself is the artifact. These include the room where Beck tried to kill himself and Stauffenberg’s corner office of the third floor, likely where he was when he was arrested and taken down to the courtyard with his colleagues to be executed. The museum is a history lesson; a slow, contemplative walk to read and think about the thousands of individual stories of resistance to Nazi fascism.

I won’t do much talking here, just take some time to finish our tour today to understand the acts of resistance, small and great, some planned, some spontaneous, many, perhaps most, never to be known. There are two great lessons, as far as I am concerned. One is that the ubiquitous, totalitarian nature of fascist power does not allow people to coalesce, to share their thoughts of opposition with others. Many acted as individuals or in very small groups, never knowing there were others doing the same. Persecution and the threat of worse kept them isolated and feeling alone.[17]

The other is limiting of free speech and action, either self-imposed or enforced through the most innocent of ways. The story of Elfriede Scholz, the sister of great novelist Erich Maria Remarque, is most illustrative. Remarque, whose first novel, All Quiet on the Western Front burned in the Opernplatz, was arguably the person most hated by the Nazis – left Germany well before Hitler came to power and spent the rest of his life in exile writing novels chronicling the history of Germany through experiences of individuals’ lives.

Scholz made an offhand observation in private at a shop in 1943 that she didn’t believe Nazi propaganda. Her remarks were reported to the local Gestapo and she ended up in court before Freisler – who presided because he knew it would please Nazi leadership that, if they couldn’t get Remarque, at least they could get his sister – who sentenced her to death for “subverting the war effort,” a common “crime” that kept the Volksgerichtshofbusy throughout the war. Scholz was executed in the same place where Hübener was, and where Wartenburg and many others convicted for the July 20 plot were.

Many of the stories we’re reading about as we walk through the Resistance Museum had the same fate at the same place: Plötzensee Prison. I’ll talk about some of them tomorrow, for the last part of our tour. For today, however, we’ll finish here.

Too bad we can’t end the day by meeting up again for an evening of music at the Konzerthaus or the Berlin Philharmonic. It would have been a fitting conclusion to an intense day. Listening to something like Mahler’s or Mendelssohn’s respective 2nd symphonies, would help us to reflect on what we saw today. Even Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony would have been appropriate. It commemorates Babi Yar, the massacre of 34,000 Jews on September 28-30 outside of Kyiv, Ukraine – which, tragically, is now just one of the centers of global atrocity that plague our world today.

But since there isn’t a concert, perhaps we could finish the day by listening to a short piece composed by a Black American, Julia Perry, who grew up and died in the town where I now live and from which I am writing. Ye, Who Seek the Truth embodies the purpose of our walk today. I’ll text you a link to a recording.

Unimaginable acts of barbarity and injustice against our fellow men and women are never as far away as we might want to believe. We only (only! – as if it were that easy) have to muster the courage and conviction to be ever-vigilant, become aware, and substantively pledge not to accept them.

I’ll see you tomorrow morning at Plötzensee, a place I feel compelled to make a pilgrimage to whenever I have the opportunity to be in Berlin. I’ll send you the location to where we’ll meet. It’s about fifteen to twenty minute cab ride northwest of the Reichstag building. See you soon.

War, along with fear, reaches you in an instant. It penetrates walls, it moves over mountains, through rivers. It enters the human mind, human hearts, human souls. It settles there and will not leave.

~ Daša Drndić, EEG

[1] From 1954 to 1990, the day of commemoration was observed on June 17. I’ll come back to that in an upcoming story.

[2] I prefer the term conspiracism, coined by Thomas Milan Kunda, a retired professor from Plattsburgh, New York, rather than “conspiracy theory” because it is more accurate. The word “theory” alone implies a certain logic and legitimacy, which, in this case is not earned or valid. A conspiracism, on the other hand, is “a mental framework, a belief system, a worldview that leads people to look for conspiracies, to anticipate them, to link them together into grander overarching conspiracy.” From Conspiracies of Conspiracies: How Delusions Have Overrun America, University of Chicago Press, 2019.

[3] The first concentration camp, Dachau, northwest of Munich, was established on March 22, 1933, less than two months after the Reichstag Fire. Journalists, socialists, and communists, all considered to be the immediate threats to Nazi hegemony, were the first victims. Ossietzsky was sent to camps in northern Germany.

[4] Brandt was later the mayor of West Berlin who became an international figure when the Berlin Wall went up. He was the first social democrat to become German chancellor. His policy of Ostpolitik in the early 1970s is considered by most historians to have been the beginning of the end of the Iron Curtain and the Soviet Union.

[5] The Opernplatz has been renamed the Bebelplatz, after August Bebel, one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party. All the buildings were restored after being bombed in World War II.

[6] After Hitler’s ascendancy to power, all newly married couples in Germany during received a copy of the book. I bought a facsimile copy in, of all places, a Borders bookstore in West Hollywood, California in the mid-1990s.

[7] Richard Evans, The Hitler Conspiracies, Oxford University Press (2020), p. 48.

[8] Freisler was one of the participants of the Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, when the Final Solution to exterminate European Jews and other “undesirables” was initiated and planned.

[9] „Freisler wollte ein Justiz, die schnelle und harte Urteile fällt. Vor allem gegen ,politische Verbrecher’, für Freisler die schlimmsten Verräter und Staatsfiende.“ Helmut Ortner, Der Hinrichter: Roland Freisler – Mörder im Dienste Hitlers, Nomen Verlag (2022), p. 94.

[10] Ortner, p. 173.

[11] Hübener was a Mormon from Hamburg, but that was not the reason for his conviction. Unlike Jews, Roma, Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses, liberal Catholics or Protestants, homosexuals, or political opposition, Mormons were treated like all other Germans and not persecuted for their faith. Hübener was convicted of building an illegal radio receiver, when he was sixteen, to listen to BBC broadcasts. He, along with three friends, who were not sentenced to death and served in the German military, printed flyers and placed them in phone booths and public busses in an effort to inform others about the lies of German propaganda.

[12] „Eine ganz kleinen Clique ehrgeiziger, gewissenloser und zugleich unvernünftiger, verbrecherisch-dummer Offiziere…“

[13] Moltke’s great uncle, Helmuth von Moltke (the Elder) was chief of staff of the Prussian army from 1857-1871 and the German army from 1871-1888. His uncle was Helmuth von Moltke (the Younger), who served in the Franco-Prussian War and was chief of staff of the German army from 1906 until just after the beginning of World War I in 1914. Moltke’s mother was from South Africa and he attended Oxford University.

[14] The Confessing Church (die Bekennende Kirche) is often translated into English as evangelical church, causing the contemporary American politically active evangelical movement to claim him as one of their own, but in reality, Bonhoeffer believed in keeping faith separate from partisan politics.

[15] The same was true in the United States. Americans who volunteered for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to fight against the fascist forces of Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) were prohibited from serving in the American military after the United States’ entry into World War II because they were considered to be “premature anti-fascists.”

[16] „…die Kommunisten waren ja keine Freunde der Kirche, sondern im Gegenteil ihre erklärten Feinde, und deshalb haben wir geschwiegen. Und dann kamen die Gewerkschaften, und die Gewerkschaften waren auch keine Freunde der Kirche, und wir haben wenig Beziehungen oder gar keine mehr gehabt und haben gesagt, also lass die ihre Sachen selber ausfechten.“

[17] In my opinion, Hans Fallada’s (pen name for Rudolf Ditzen) novel, Jeder stirbt für sich allein (translated as Alone in Berlin), is the most impactful description of what living under and resisting against Naziism was like for average persons.

The history to me reminded me of the MAGA world of today. Will our democracy prevail?